|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | GRANTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

Professors in new education center tackle behavior problems in schoolsby Scott Brinckerhoff - September 10, 2007 | ||||

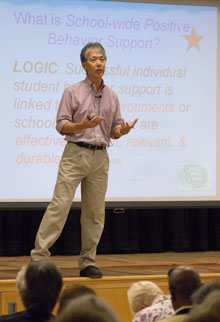

| UConn’s George Sugai and his colleagues at the Neag School’s new Center for Behavioral Education and Research have embarked on a daunting mission: to help U.S. schools improve their teaching environments and adopt ways of positively addressing problem behaviors. Against a backdrop of negative headlines about violence in schools, mediocre test scores, and escalating school budgets, Sugai’s approach to improving education is easily summarized, but perhaps not so easily implemented. “Our Center focuses on establishing safe and positive school climates where problem behaviors are addressed in a constructive, rather than punitive manner,” Sugai says. “To develop a sense of shared responsibility and maximize success, schools must include everyone, from bus drivers to principals, family members to paraprofessionals, security guards to substitute teachers,” he says. “Everyone needs to believe that all students can thrive and learn vital social skills in their school.” Sugai came to UConn two years ago from the University of Oregon, whose special education programs are ranked among the top in the country. He has published extensively and is one of the nation’s top experts on classroom and behavior management, school discipline, and educating students who demonstrate “at-risk” behaviors. He holds the Carole J. Neag Endowed Chair at the Neag School of Education, and has helped establish the new Center for Behavioral Education and Research which includes UConn researchers such as Sandra Chafouleas, Michael Coyne, Mike Faggella-Luby, and Brandi Simonsen. Sugai also co-directs the National Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, which is funded by the U.S. Department of Education to conduct research and disseminate “best practices” to schools around the country. The PBIS Center supports nearly 6,000 schools across more than 40 states. When Sugai looks at U.S. schools, he sees places that can enhance the academic and social needs of all students and be a resource to communities-at-large. He believes schools often fall short because they emphasize a “get-tough” approach to discipline rather than teaching and encouraging student social skills associated with respect, responsibility, safety, and relationships. Sugai stresses that giving school, family, and community members the tools to create constructive teaching and learning environments is one of the best ways to improve the surroundings for all students. In addition, it can often prevent antisocial behavior. Although metal detectors, security personnel, and surveillance cameras may be necessary in some places to ensure safety, they are no substitute for a school climate where academic and social instruction are paramount. Many students come to school prepared to learn and ready to accept disciplinary rules and consequences for violating them. But some students do not conform, and need additional support rather than tougher, more severe consequences. Sugai and his colleagues have seen what happens when schools fall into the trap of “getting tougher.”

For example, in one academic year, a school of 800 students processed 5,000 office discipline referrals for major rule violations. In another district, more than 400 kindergartners were expelled. A teacher in one school sent students to the school administrator more than 250 times for classroom disruptions, and at another, one student was sent to the office or in-school suspension room more than 49 times. Of such cases he says, “The research is clear – if the primary or only way of responding to bad behavior is punishment, the problem is exacerbated, not resolved.” Sugai says school climates can improve when students are involved in activities such as drafting a code of conduct, identifying positive school values, and developing lessons for teaching those values. Students who participate in such ways, he says, are more engaged, disrupt teaching less, and are generally better behaved – all of which results in improved academic achievement. Unacceptable behavior can be found to some degree in all sorts of schools – urban poor, isolated rural, crowded suburban. But when classrooms, hallways, and lunchrooms are predictable and upbeat environments, students can be taught to adjust their behavior to local expectations. Sugai says he has seen schools with healthy climates where kids soften their demeanor and their language the minute they walk in the door. The PBIS approach involves frequent and sustained training in which the emphasis is on giving local staff the capacity to establish effective practices. Sugai acknowledges that change is difficult. But in some states, schools have accepted the training protocol with enthusiasm. One year after training, schools in those states experienced a decline in “problem behaviors,” a better self-perception of safety, better quality attention given to youngsters who did exhibit behavior problems, and noticeable gains on statewide achievement tests. Much of what Sugai has to say sounds like common sense and it is, says Richard Schwab, dean of the Neag School of Education. He applauds Sugai’s “holistic” and evidence-based approach to fixing the nation’s schools. “George is doing a brilliant job, and he’s also helped attract some bright young talent,” Schwab says. “They’re doing excellent research in all sorts of areas, including early literacy, classroom management, early vocabulary development, and adolescent literacy.” |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |