|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | GRANTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

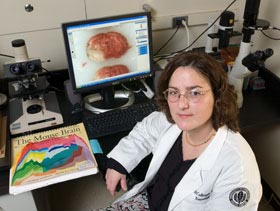

Neurologist studies why more women than men have strokes

by Carolyn Pennington - February 13, 2006 |

||||

|

Many women think stroke is a men’s disease. But the truth is that more women than men will die from it. Of the 700,000 Americans who have a stroke each year, 39 percent of those who die are men and 62 percent are women, according to the National Stroke Association. And even though death rates for heart disease and stroke are declining in men, this advance has not been evident in women. “Both stroke incidence and mortality have increased in women over the past three decades,” says Dr. Louise McCullough, director of stroke research at the Health Center. The relationship between stroke and gender has historically been an understudied topic. McCullough, a board-certified vascular neurologist as well as a basic science researcher, is actively investigating the effects of gender on both clinical and experimental stroke. A stroke is a form of cardiovascular disease that affects the arteries traveling toward and inside the brain. A stroke results when one of these vessels becomes blocked or bursts and the brain is deprived of blood and oxygen. Why are more women dying from stroke than men? Is it because women live longer and are more likely to experience a stroke when they’re older and frailer? Or is it because they are less likely to receive some of the diagnostic tests? These are some of the questions McCullough is trying to answer. Researchers long assumed that estrogen plays a protective role, since women tend to experience strokes later in life when hormone levels begin to decline. But the Women’s Health Initiative, a randomized clinical trial designed to research estrogen and stroke, revealed that women who received hormone replacement therapy had higher stroke rates than those who were treated with a placebo. And aside from hormones, McCullough has found females tend to be protected from stroke whether estrogen is present or not, suggesting that protection may occur on a chromosomal level. “In the lab, if you take female cells and grow them in a dish and expose them to a stroke-like injury, they do better than cells from a male. This suggests it’s not just the hormones, because these cells are not exposed to hormones,” she says.

As a researcher, McCullough studies some of the potential differences on the genetic level. As a clinician, she compares stroke treatment for women and men. Studies have found that women are less likely to be prescribed blood pressure meds or be advised to take aspirin, both of which reduce stroke risk. This is true even for women with known cardiovascular disease. Women are more likely than men, however, to receive anti-anxiety medication. Using tissue cultures or animal models, McCullough says, it has been found that certain drugs which protect male brains from stroke do not protect female brains. She says that’s why clinical trials need to be carefully considered before testing them on humans. In the future, she says, gender-based designer drugs may be the answer. McCullough notes that lifestyle changes that can lower the risk of stroke. Some risk factors are the same for men and women: high blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking, diabetes, obesity, and not exercising. Unique risks for women are: birth control pills, hormone replacement therapy, a thick waist and high triglyceride level, and migraine headaches. Common stroke symptoms in men and women include weakness or numbness in the face, arms, or legs, especially on one side of the body; visual changes in the eyes; severe headache; dizziness or loss of balance; and trouble speaking or understanding. Unique warning signs for women are sudden hiccups, nausea, chest pain, and shortness of breath. “Too many women ignore the symptoms,” says McCullough. “Many have told me they thought their symptoms would disappear if they took a nap or rested awhile. Then by the time they get to the emergency room, it’s too late.” |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |