|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | GRANTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

Nursing professor develops medication management softwareby Beth Krane - September 15, 2008 |

|||||||||

| Before tablet computers were on the market, Patricia Neafsey envisioned a user-friendly software program for older adults to learn more about their medications and potentially dangerous drug interactions.

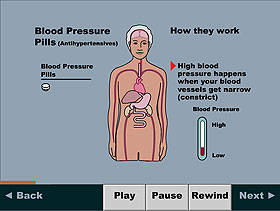

Neafsey, a professor of nursing and a principal investigator at UConn’s Center for Health, Intervention, and Prevention (CHIP), began by developing the program for individuals with hypertension. “Patients with hypertension are an important population to study because they will have to take medication the rest of their lives,” she says. “If this kind of intervention is going to work, it should work with this population and this kind of chronic disease.” For a study of the initial version of her software, Neafsey attached touch screens to laptop computers with Velcro. Older adults with hypertension completed paper-and-pencil surveys about their medication use, and then used the modified laptops to view a series of animations about blood pressure medicines and drugs that could interact with them. With the help of a $1 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, Neafsey’s software has evolved to match her original vision. She now is testing her “Personalized Education Program-Next Generation” (PEP) through a clinical trial involving 264 patients with hypertension age 60 and over at 11 primary care practices across Connecticut. She says more than 90 percent of adults age 65 or older take at least one medication daily, and almost 60 percent of adults in that age group take five or more medications daily, including over-the-counter medicines and herbal supplements. “Many of these agents can interfere with antihypertensive medications,” says Neafsey, who has a doctorate in pharmacology. Many patients do not know, for example, that ibuprofen actually elevates blood pressure on its own, and also counteracts the effectiveness of antihypertensive medications, she adds. The program, which contains more than 1,600 ingredients and 183 adverse self-medication behaviors in its database, runs on a touch screen tablet computer that patients can use while waiting in doctors’ offices for routine medical appointments. Each patient answers questions about his or her medications on the touch screen. The program then ranks the medication behaviors by degree of risk, and delivers tailored, interactive educational content about them.

It also provides the patient’s doctor or nurse practitioner with a summary before they see the patient, so they can discuss the issues during the office visit. A team of UConn researchers helped develop the program, including co-investigator Carolyn Lin, a communications sciences professor, Elizabeth Anderson, an associate professor of nursing, and Sheri Peabody, a graduate student in nursing. In a test, Neafsey found that nine of 11 patients achieved lower blood pressure readings after using the software during just three regular office visits. Neafsey is also mentoring two nursing honors students who are conducting a pilot study involving UConn employees age 45 to 60 with hypertension to learn whether the software needs to be adapted for people under 60. The project, which has 11 participants, is receiving computer and statistician support from CHIP, and uses space at its offices. Gregory Lutkus, an honors student in nursing, says PEP is extremely comprehensive. “It is next to impossible to find a medication Dr. Neafsey didn’t include in the program, which is especially impressive considering the vast number of medications in existence,” he says. Lutkus and fellow nursing honors student, Jessica Newcomb, have been involved in every phase of the honors research project. Both the clinical trial and honors research project are scheduled to conclude by the end of the year, Neafsey says, and the results from the honors research project may be used to support her team’s next application for federal funding to continue developing PEP. Neafsey hopes ultimately to adapt the program for patients with other chronic medical conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes, as well as those with hypertension. |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |