|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | GRANTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

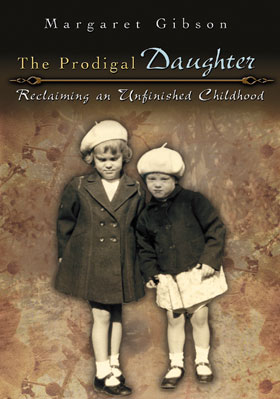

Memoir recounts Southern childhood and family differences

| ||||

| Margaret Gibson’s parents often referred to her as their Connecticut Yankee daughter. Although she was raised in Richmond, Va., Gibson moved to the Northeast after college, leaving behind Southern customs and culture she could not embrace. Gibson, an emeritus professor of English and noted poet, tells the story of her life in her new memoir, The Prodigal Daughter, Reclaiming an Unfinished Childhood, published by the University of Missouri Press. The book follows on the heels of her ninth book of poems, One Body, which was published last year. Gibson and her sister grew up during the 1950s in what she calls a “southern and very traditionalist, conservative culture. “My sister stayed in Richmond and lived a very conventional married life and didn’t change her views about the social and political world,” says Gibson. That world was defined by racial segregation, the division of rich and poor, and a strict fundamentalist religion. “I was coming of age during a period when real changes in society were beginning to happen, particularly in the area of integration,” she says. When she reached her teens, Gibson became acutely aware of the differences between herself and her family. “I realized that the reasons for segregation were not valid,” she says. “The changes I went through during the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War put me over on the left. My parents didn’t understand that. Also, I wanted to become a poet, and my parents didn’t understand that either. “I grew up in a culture in which to say you were different from someone meant that you didn’t have to deal with that person,” Gibson says. “The natural differences with my sister became magnified by the fact that I grew up in a culture in which division and separation was the normal state of affairs.” She adds: “Most of my rebellion was interior, and rather than remaining in Virginia to try to change things, I left.” Gibson says the opening and closing chapters of The Prodigal Daughter are about her restored relationships with her parents and her sister. The bulk of the book, she says “falls into the genre of childhood memoir, remembering what it was like to grow up in my particular family of origin in Richmond.”

She says she and her sister were close in age “but that was about as far as it got. We were temperamentally very different.” When her sister had a stroke in 2000, Gibson went to Virginia to help her. “My sister had become totally dependent,” she says. They spent a good deal of time talking about their childhood, and became friends. “My big discovery – it took my breath away - was that underneath all this difference, I had always loved my sister,” Gibson says. In the opening chapter of the book, Gibson recounts a visit to her sister following the stroke. She writes: “As I massaged her legs, as my body faintly rocked back and forth to increase the rhythm, all the years I forgot to remember her, all the years I scorned and disregarded part of my own heart, fell away, and it came to me in a shudder of surprise that I had, all these years, loved her without knowing that I loved. What was it in me that had concealed that love so stubbornly? How was it possible to love and not to know?” Gibson says writing a memoir “helps you as much understand yourself as you are now, as it helps you understand the way you were then. It’s as if in recreating the voice and the context and the character of who you once were, you become more able to understand who you are and the distance you’ve come.” She says writing a memoir was much harder to write than poetry in one respect: “When you write a memoir, you make a pact with the reader that you’re going to write what really happened. You may compress things to make it a work of art, but you tell the truth.” That wasn’t always easy, she adds: “I thought, ‘Am I really going to write about my father’s nervous breakdown? Is that too private?’ But making the pact to tell the truth means that you walk around with a little bit more of yourself out there than you might like.” |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |