|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | GRANTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

U.S. must address tarnished human rights reputation, speaker says by Elizabeth Omara-Otunnu - October 9, 2007 | ||||

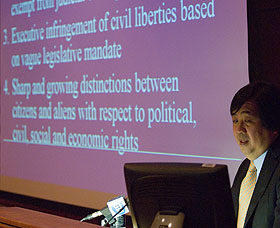

| Policies pursued by the United States since Sept. 11, 2001, both at home and abroad, have tarnished the country’s human rights reputation, according to Harold Koh, dean of the Yale Law School. And, he says, restoring it will take a concerted effort across all branches of American society. Koh made his remarks during the 13th Raymond and Beverly Sackler Human Rights Lecture, “Repairing Our Human Rights Reputation,” at the Dodd Center Oct. 2. He said that before Sept. 11, an international vision prevailed that included diplomacy backed by force as a last resort; human rights based on universalism; and a belief, promoted around the world, that democracy is the best way to bring about human rights. Just six years later, he said, the world has been turned upside down. Too often, the United States uses force first, accepting preemptive strikes and wars of choice; our human rights policy rejects universalism (“the only freedom we care about now is freedom from fear,” he said); and our foreign policy is characterized by antipathy to international law and indifference to global cooperation. “Who knew so much damage could be done in such a short period of time?” Koh said. Not only has the country’s international vision been inverted, he said, so has our constitutional vision. Six years after 9/11, Koh said, there is unfettered executive power; law-free zones (military commissions) that are exempt from judicial oversight; executive infringement of civil liberties based on a vague legislative mandate; and sharp and growing distinctions between citizens and aliens. He said the U.S. is increasingly seen as hostile to human rights. The incidents at Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison suggest that the U.S. has moved from zero tolerance of torture to zero accountability, he said: “Privates in the army have been tried and convicted, but no one higher up.” Torture has been redefined, and “public acceptance is growing that torture is inevitable and justified in the war on terror.” In the TV series 24, for example, which averages 15 million viewers in the U.S., government officials are regularly depicted as justifiably committing war crimes. Even America’s closest allies no longer regard us favorably, Koh said. For example, 85 percent of Germans now believe U.S. policy involving prisoners held at Guantanamo, Cuba, is illegal, and 65 percent of people in the U.K. think the same. Guantanamo, where no prisoner has been tried and no one has been convicted, “created a human rights black eye for the U.S.,” he said. “Cuba, Iraq, and Guantanamo are taking us from the moral high ground. Our global image has slipped.” Koh said there is some hope in the response of various parts of civil society that “have come back to object.”

The news media, for example, were responsible for bringing Abu Ghraib to public attention, he said, and the country’s librarians, among others, banded together to force changes to the U.S. Patriot Act so that certain private records would not be disclosed, as originally had been proposed. Koh said a 2006 Supreme Court case, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, which invalidated military commissions, was a turning point. Military commissions afford fewer civil rights than regular trials, and were part of the Bush administration’s plan to deal with detainees it links to al-Qaeda. The lessons from Hamdan are much bigger than military commissions, he said. The case indicated that the President’s response to terrorism must fit within the fabric of existing statutes and treaties. If the United States acts upon the principles stated in the Hamdan decision, he said, it will enable the country to turn what is now upside down, right side up again. “We need to get ‘back to the future’ to reassert the basic principles of truth telling, universal standards, accountability, curbing ongoing abuses, and preventing future abuses,” Koh said. In recent years, he said, the United States has adopted a double standard with regard to human rights, failing to hold its allies accountable for their abuses, or to address America’s own abuses. “There has been a sad failure to endorse universal standards,” he said. President Bush withdrew the country’s signature on the International Criminal Court treaty, Koh noted, and has undermined United Nations mechanisms for the protection of human rights. And the U.S. still has not ratified the Treaty for Elimination of Discrimination against Women or the Convention on the Rights of the Child. “My daughter’s mother is from Ireland,” Koh said. “If she was living there, she would be protected. Here, she is not.” He said the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial branches, and civil society, all have a responsibility to bring the U.S. back into compliance with the rule of law. “Ours is a country founded on human rights,” he said. “If we violate these human rights, we no longer know who we are.” |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |