For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page.

Jaw Pain Study Explores Effectiveness

Of Non-Surgical Treatments

A Health Center study on jaw pain, or temporomandibular disorder (TMD), arms its participants with tools ranging from biofeedback and meditation to physical therapy, as well as medication, in an effort to establish which of these approaches is most effective.

|

Mark Litt, a professor at the Health Center, is conducting a federally-funded study of non-surgical treatments for jaw pain.

|

The five-year study is looking at non-surgical treatments for TMD, an often disabling condition that affects between 5 percent and 12 percent of the adult population, usually in their 20's or 30's, and costs billions to treat every year.

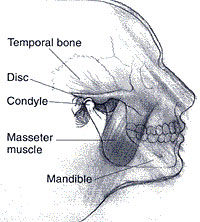

"The condition can be marked by pain that prevents people from chewing or talking," says Mark Litt, a professor of behavioral sciences and community health who is principal investigator for the $1.69 million study. "Other symptoms include clicking or popping or the jaw locking in an open or closed position, but it is usually the pain that gets people to seek treatment," says Litt.

"Although the dysfunction is often caused by problems between the discs of the upper and lower jaw, the pain is not usually caused by joint damage," he says. "Surgical treatments aimed at fixing discs or repairing the joint often have not been very effective. Surgical treatments should probably be viewed as a last resort."

Health professionals have turned to non-surgical treatments like psychotherapy, biofeedback, physical therapy, and meditation to get sufferers to relax the large muscles of the jaw. "Interestingly, all of these things work for some people suffering from TMD," Litt says. "The purpose of our study is to try to determine which of these non-surgical treatments are most useful."

All the participants in the study, which began last summer, are examined by an oral surgeon. They are given anti-inflammatory medication to take around the clock, are advised to eat a soft diet, and are fitted with a clear plastic splint to wear so their top and bottom teeth don't touch. They are sent home with a cell phone.

Four times a day, participants receive calls from a computer program that asks them what they are feeling. It asks them to rate their pain on a scale from zero to six and whether they have taken steps to manage the pain. Those steps may include taking medication, using meditation, or distracting themselves by getting a drink or watching television.

Some of the participants are given additional training to help them cope, including biofeedback, which trains them to relax the jaw muscles using a device that tells them when the jaw is tense or not.

"Our strategy is to give participants real tools and strategies for dealing with the pain and to monitor their use of those tools," says Litt. "We want to get them to change their thoughts about their pain and help them understand their own behavior. It's a combination of getting them to relax those muscles and change their oral habits. In many cases, participants don't realize they are clenching those large chewing muscles. In order to stop the habit, they have to be made aware of it."

The study is funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.