|

This is an archived article.

For the latest news, go to the Advance

Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. | ||

|

Making a

Difference in the Life of the Nation

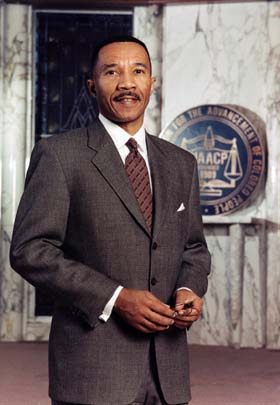

A person's life is recorded on his or her tombstone by three things: the date of birth, the date of death, and a dash in between, according to Kweisi Mfume, president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, America's oldest and largest civil rights organization.

Speaking in Konover Auditorium November 8 as part of the University's Human Rights Semester, Mfume said the dash represents the person's life: "The definition of that dash is what we live day in and day out." Although you don't have much choice about the dates, the dash is what you make of your life, he added. "It represents your chance to make a difference." Mfume said the NAACP is trying to make a difference in the life of the nation. Since it was founded 90 years ago, it has seen America through the years of Jim Crow, lynchings, disenfranchisement, and other forms of discrimination against African Americans. The organization has "tried to help a nation divided against itself," he said. But although the history of the NAACP is "filled with major accomplishments that have changed for ever the America we know and love, ... it is not a matter of having come a long way, but of having a long long way to go," he said. "Our assembled diversity has produced the most successful experiment in democracy in the world's history." Yet differences of race, religion and ethnicity, and between the haves and have-nots, have led to alienation. "America at her best has treated those differences with a blend of common sense and compassion," he said, "at worst with the empty even-handedness of Marie Antoinette, who said 'let them eat cake.' "The differences between groups in society are not novel or new," Mfume said, but in the wake of September 11, "our approaches to those differences must be both." He said September 11 changed all our lives. "All of a sudden, we woke up to 911. We instantly began to yearn for the good old days when things were simpler. "After watching about 5,000 lives snuffed out, the little things seemed more important than they ever did," he added. "We took longer to hug our loved ones as they left the house. "The good old days are not coming back," Mfume said, "but the problems we faced before September 11 are still with us." He noted the continuing disparities in income, and cited statistics on differences in the health status of different racial groups. The rate of breast cancer among black women, for example, is three times the national average, and black men suffer from prostate cancer at eight times the national average, he said. In addition, hate crimes continue to be a significant problem, yet Congress has failed to gather sufficient sponsors for a bill against hate crimes. The question we must ask about Sept. 11, is "Did we learn enough from that incident to understand that at the end of the day we're all still Americans, our similarities outweigh our differences?" he said. "The answers are not without, they are really within. Unless we are prepared to deal with differences and build in a constructive way on our similarities, we will always be vulnerable to things that keep societies from realizing their true greatness," he said, "there will not be much definition for the dash, as individuals or as a nation." Elizabeth Omara-Otunnu |