This is an archived article. For the latest news, go to the Advance Homepage.

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page

| |||||||||||||

|

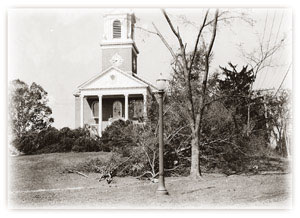

September 21, 1938, the day of The Hurricane, must have been a busy day for Jerauld Manter. The Connecticut State College faculty member was the official photographer for the campus and he spent much of the day getting photos of storm damage around eastern Connecticut.

Throughout the region and the state, rivers and streams were near flood stage. Dams were overflowing. Some dams were breaking. Barns and homes were badly damaged. Livestock had been killed. Manter's photos were of damage caused by five days of torrential rain that soaked New England. He wanted to document as much of the aftermath as possible. But, like everyone else that last day of summer in 1938, Manter didn't know the region's troubles were far from over. As the hurricane approached, students were heading for Storrs for the beginning of fall classes. Registration for new students was the day of the hurricane, and freshmen had been arriving since Monday, September 19. Returning students were to register September 22 and classes were scheduled to begin Friday, September 23. On the day of the hurricane and the following day, about 300 students arrived on campus. "One group (of students), after traveling 50 extra miles to get across the raging Connecticut River, was forced to remove shoes, socks and trousers to wade across the Willimantic River," on their way to Storrs," according to an article in the first regular issue of the student newspaper, the Connecticut Campus for the fall semester, published October 4, 1938. What students found as they arrived was a campus without electricity or telephones, no water, and hundreds of trees blocking roads and walkways. There was also a concern about food shortages, but the campus managed with a delivery of meat from the Norwich area. With no telephones, one student rigged up a ham radio and a generator to get messages out of Storrs to students' worried parents. Using the one antenna on campus that had not been blown over, and two batteries - one pulled out of a car - Ronald Rast, a senior from Terryville, worked into the night after the hurricane to set up his amateur radio. He then sent word to the state's disaster headquarters about the campus's need for water, and sent a story on storm damage to The Hartford Courant. The message was relayed via a shortwave station in West Hartford that picked up the signal of Rast's 10-watt transmitter.

At least 40 messages were sent by Rast. More than half the messages went to parents as far away as the Maine coast and York, Penn. By Saturday, the main power lines to the campus Dining Hall and the Fenton River pumping station were restored. Most power was restored to the campus by October 1. But by October 4, although calls could come in to the main switchboard in Beach Hall, there was only one other working phone on campus, in Holcomb Hall. With telephones down, campus communications continued through special editions of the Connecticut Campus, normally a weekly during the semester. Following the hurricane there were several extra editions, printed on a hand-cranked mimeograph machine. The first is dated September 22 - the day after the hurricane. Sometime on Thursday, the day after the storm, two students undertook to catalog the damage. Barbara Everett (Fitts), Class of 1939, and Rodman Longley, Class of 1940, split up the campus and recorded every fallen tree - 42 species in all. On the north end of campus, Everett counted 15 trees down on what was referred to as the front campus - the green area along Route 195 from North Eagleville Road to just north of Mirror Lake. Twenty-nine trees were down between Beach Hall and North Eagleville (at the time, only the Duck Pond - now known as Swan Lake - was between Beach and the road). But this was just the beginning. Between the dining hall and the heating plant, Everett counted 527 trees uprooted or snapped like sticks. In all, she counted 1,112 trees down. At the south end of campus, Longley counted 150 trees down in the grove north of Mirror Lake. Over on faculty row, he counted 220 trees down. His total was 650. Combined, Everett and Longley cataloged 1,762 trees, only a few of which would be saved. A series of photos by Manter shows one uprooted birch tree, located on the front campus across from what is now the Honors House, being pulled back into place. But most of the trees were total losses. An oak honoring alumni and students killed during World War I was destroyed. At the Valentine Grove, an area that included many oaks and in which early commencements were held, 116 trees were demolished. There was no loss of life at the college, and no severe injuries recorded (throughout the Northeast, however, hundreds lost their lives and thousands were injured). But there was quite a bit of damage to facilities: the estimated cost in 1938 dollars for damage to dormitories, barns, and other property, excluding trees, was put at $87,065 (with trees, the loss was later said to be nearly $250,000). Twenty-two of 26 hen houses were leveled and 200 hens, 40 percent of the flock, were killed. The International Egg Laying Contest, a program on campus for more than 50 years, fared a little better - all 50 contest houses held up to the storm, and only 70 of 1,000 birds died. Birds had been sent to Storrs from 15 states for the annual contest and, despite storm damage, they had to be returned to their owners. The Connecticut Campus reported that years of research in the Animal Diseases Laboratory was lost: 300 chickens were killed, and 600 to 800 suffered from exposure. Eleven wooden research structures used by Animal Diseases were destroyed. Albert Moss, a professor of forestry, later noted that he had found salt spray from Long Island Sound as far inland as 45 miles, damaging a large number of trees. Two short items in the Connecticut Campus give chilling gimpses of the strength of the storm. One noted that slate, which "hurtled from roofs like machine gun bullets, is being withdrawn from walls." They were brick walls. The other item is written in a light-hearted vein, challenging the description of the storm as a hurricane and posing the suggestion that perhaps it was a tornado: "The proof: While the houses still standing at the poultry plant were being surveyed after the blow, a couple dozen light bulbs were found on the floor - intact. When the clean-up squadron replaced the errant bulbs after the power was restored, it was startled to find them still in good condition. "Quite a wind to unscrew those bulbs; in fact, some 'twister'." Yet despite all the damage, the loss of electricity and telephones, and hundreds of trees down, classes for the Connecticut State College student body of 1,050 began as scheduled at 8 a.m., on Friday, September 23. Mark J. Roy Sources: Issues of the Connecticut Campus, Sept.-Dec., 1938; special editions of The Hartford Courant and The Hartford Times, October 1938; Jerauld Manter photograph collection for the Hurricane of 1938. "Trees Destroyed by Hurricane, Connecticut State College Campus, September 21, 1938," by Barbara Everett and Rodman Longley. All these materials are in the collections of the University Archives at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. |