|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | GRANTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

Linguistics experts compile database to compare international sign languages by Elizabeth Omara-Otunnu - October 6, 2008 | ||||

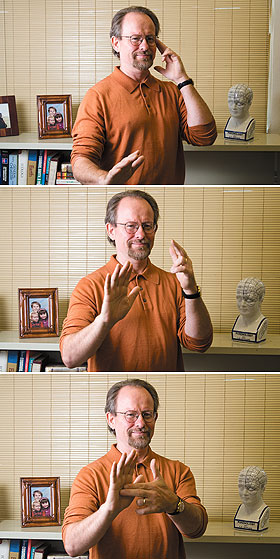

| Two researchers in the Department of Linguistics are engaged in a comparative study of sign languages from around the world. With support from a two-year, $200,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, Professor Harry van der Hulst and Rachel Channon, a research specialist, have compiled a database that contains information on nearly 12,000 signs from six different sign languages. The initial goal of the project, says van der Hulst, is to understand through quantitative analysis how sign languages differ in terms of the visual images they use. The next stage will be to draw theoretical conclusions from those differences. The information recorded includes hand shape, movement, location of the movement, and other characteristics for each sign. The database, known as SignTyp, uses Excel software and will be posted to the Web as a resource available to any researcher interested in sign language. “We tried to make it as user-friendly as possible,” says van der Hulst. The database consists of collections gathered by sign language specialists around the world, the largest being a database of Sign Language of the Netherlands that van der Hulst compiled in his native Holland before coming to UConn in 2000. The others include American Sign Language (both current and historical), Finnish, Japanese, Korean, and New Zealand sign languages. Because they were developed independently, each collection used a different coding system. One of the challenges of the project, says van der Hulst, was to design a universal coding system and then translate the information about each sign recorded. The researchers have already begun to analyze which hand shapes are used in each particular sign language, and to explore issues such as how these building blocks are combined. Van der Hulst says the study of sign languages is a relatively new field that emerged only in the past 50 years. “Sign languages – languages used by deaf people – are in linguistic circles considered to be full-fledged human languages,” he says. “But this view has not been around that long. And still, outside linguistic circles, people may think of them as gestural communication systems without grammatical structure.” Van der Hulst specializes in phonology, which strictly interpreted refers to the study of the sounds that are the building blocks of words. “When I started studying sign languages, it changed my perspective on what human languages are,” he says. “Sign languages are extra interesting in the domain of phonology, because the medium is not sound but visual display.” Van der Hulst says sign languages have comparable building blocks to those that make up words in spoken languages – visual images. They also have rules for combining words into sentences, known as syntax.

Linguistics, he says, has traditionally focused on sound: “It was once thought that language has to be speech. Now we learn that language does not have to be speech, it can also be gesture. And the view that all languages have consonants and vowels no longer holds, because consonants and vowels are speech entities. “So linguistic theories have to step up to a more abstract level,” he adds. “That has had enormous implications for how I think about phonology, which we should now define as the study of the perceptible form of language.” The UConn linguistics department in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences is one of the few linguistics departments in the world where sign languages are a specialization. In addition to van der Hulst, Professor Diane Lillo-Martin studies the structure of sentences in sign languages. The department also collaborates with the Department of Modern & Classical Languages, which has an American Sign Language (ASL) program taught by Doreen Simons-Marques. During the summer, van der Hulst and Channon hosted a conference at UConn that was attended by about 80 scholars from 15 countries, including Australia, Brazil, Japan, the Netherlands, Turkey, and the UK. They engaged a team of four professional ASL interpreters to translate the spoken presentations; some of the papers were delivered in ASL. “Because our project has comparative focus, we involved in our project an impressive forum of international researchers,” says van der Hulst. He hopes that by involving sign language specialists from around the world, he can expand the project to incorporate additional languages. “Now they’ve seen the prototype of SignTyp and what can be done with it, we hope they will be willing to give us their inventories too,” he says. Van der Hulst says the number of known sign languages is in the hundreds. Currently on a one-year ‘no cost’ extension of the original two-year grant, van der Hulst and Channon are applying to the NSF for a four to five-year renewal. |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |