|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | GRANTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

Initiative educates public about lead poisoning preventionby Karen Singer - August 25, 2008

| ||||

Widespread publicity has drawn attention to lead-tainted children’s toys from China, but many people don’t know that the biggest source of lead poisoning may be lurking in their homes. A UConn program, the Healthy Environments for Children Initiative, is working to educate the public about the dangers of lead poisoning and ways to prevent it. Dangerous levels of lead can be found in paint chips, dust, and debris in houses built before 1978, when the U.S. banned lead-based paint from residential use. Today more than 300,000 children have lead poisoning, which damages the brain, nervous system and other systems, and causes lifelong learning, behavior and health problems. “Sadly, this preventable problem still exists,” says Joan Bothell, a writer and curriculum developer for the Healthy Environments for Children Initiative, a collaboration between the University’s Cooperative Extension System and the Department of Human Development and Family Studies. Since the mid 1990s, Bothell has been working with Mary-Margaret Gaudio, extension educator at UConn’s Hartford County Extension Center and a co-founder of the program, on educational materials about the dangers of lead poisoning and how to avoid them. “We try to make people aware that they can prevent lead poisoning, and that it’s not difficult,” Bothell says. The work began in 1992, when state Department of Public Health officials asked Gaudio to write some easy-to-understand fact sheets about lead poisoning. “They liked what we did,” Gaudio says. The next project was a training manual about lead poisoning. Since then, the Healthy Environments for Children Initiative has developed educational and outreach programs and materials in English and Spanish for children, childcare providers, teachers, contractors, and do-it-yourselfers, and has partnered with state, regional, and national agencies, as well as non-profits and community-based organizations.

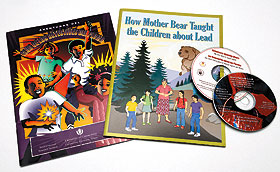

The materials include a Native American-themed curriculum for young children, “How Mother Bear Taught the Children about Lead,” that won an award from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA), and a video aimed at do-it-yourselfers, “Don’t Spread Lead.” The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has used some of the program’s materials in its National Lead Poisoning Prevention training programs. In Connecticut, the program’s 24 trainers have trained nearly 2,000 people in lead-safe work practices for painting, remodeling, and maintenance. “Lead dust is usually the major culprit for any child who lives in a house with lead-based paint that is disturbed or deteriorating,” says Bothell, adding that people who live in older houses need to learn ways to deal with lead safety issues. Other sources of lead include old furniture, toys, and jewelry. Bothell recommends checking lead recalls for consumer products at the state Department of Public Health web site. “Simple good practices” are part of the prevention process, according to Gaudio. “We tell parents to make sure their children wash their hands before meals and snacks, leave their shoes at the door, eat healthy foods, and stay away from paint dust and paint flakes,” she says. The educational materials also teach children to do some of these things themselves. HEC also administers the New England Lead Coordinating Committee, a regional consortium of state agencies working to eliminate lead poisoning, especially in children. The group held a conference on new approaches to prevent lead poisoning at the Storrs campus in June. |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |