|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | GRANTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

Donation of books on mosses expands biology collections by Cindy Weiss - March 17, 2008 | ||||

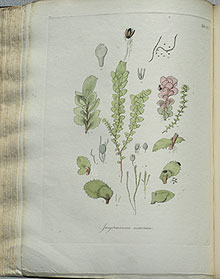

| A paleo-ornithologist who is a senior scientist at the Smithsonian Institution has donated his personal collection of books about mosses to the Biological Research Collections in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. Storrs L. Olson, the donor, assembled more than 1,000 books, journals, and reprints in the field of bryology, the study of mosses, liverworts, and hornworts. The donation, which includes books dating from the 1700s, gives the Biological Research Collections at UConn one of the most comprehensive libraries on mosses in the nation and one of the top-ranked libraries in the entire field of bryology, says Bernard Goffinet, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. Goffinet specializes in the field. The UConn collection includes one of only 251 copies in the world of a 1741 book, Historia Muscorum, as well as books from the 1800s that are housed in velvet boxes, books with delicate pressed mosses on their pages, and current books. The collection completes a set of Revue Bryologique from 1874 on, building on an earlier donation by a former Duke professor, the late Lewis Anderson. It includes a set of The Bryologist, the oldest North American journal in the field, from 1898. “It is an incredible resource for us,” says Goffinet, “– an inspiring collection of great books in the field.” The field itself has long attracted knowledgeable amateur naturalists. In the collection is a classic from 1906, Mosses with a Hand Lens, a book for amateur collectors by Abel Grout, a “grandfather” in the field of North American bryology, says Goffinet. The hand lens of moss hunters has helped amateurs and scientists identify new species, but it also has sharpened insights into evolution and biodiversity. “These organisms are shown to be the closest relatives of the earliest land plants,” says Goffinet. Books in the collection offer researchers ready access to literature that is often unavailable by loan or from the Internet. The detailed descriptions in books from the 1800s and early 1900s are invaluable to scientists today, Goffinet says. The collection has books by people who were contemporaries of Charles Darwin. It even includes a novel with the name of a moss as its title: Ulota, published in 1934 in Belfast. Olson, the donor, first became interested in mosses in 1966 when he was a student at Florida State. He gained permission to take a graduate course in bryology taught by Ruth Breen, author of Mosses of Florida, and became fascinated by the exposure to a new world of small plants. Olson went on to earn a doctorate at Johns Hopkins University. His career has focused on the study of fossil birds and island ecosystems. He is now the curator in charge of the Division of Birds at the Smithsonian.

But he remained interested in mosses, and in 1992, 20 years after earning his doctorate, he made the first purchase in his bryological book collection when Columbia University Press put a two-volume set of Mosses of Eastern North America on sale at half price. During fieldwork in Hawaii to collect fossil birds, he met the only local bryologist in Hawaii, William Hoe. They struck up a friendship. “Bill Hoe was an avid, almost fanatical, collector of bryological publications and had collected a very extensive library himself over a couple of decades or more,” says Olson. When Hoe died suddenly, his collection was passed along to his nephew, and Olson was able to purchase the bryological books. They filled two large shipping pallets with the books, reprints, and other files, which were sent to Olson’s home in Arlington, Va. He says it took him months to unpack. About three years ago, he moved from Arlington to smaller quarters in Fredericksburg, and decided that it was time to fulfill his longstanding plan to donate the collection. Goffinet, the only bryologist at UConn, heard about Olson’s plan and wrote to him about research that he was doing in Chile, where mosses are prevalent and diverse. Olson had considered giving his collection to Chile but decided to donate the collection here instead. “He wanted to see the library being used by students in the field,” Goffinet says. Goffinet’s research group includes two Ph.D. students and a postdoctoral researcher. Much of his work centers on far southern Chile, where mosses are the dominant plants. Goffinet and John Silander, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, are among the co-authors of a new paper in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment that calls Cape Horn and southern Chile a “hotspot” for bryophytes and non-vascular plants. (The lead author, Ricardo Rozzi of the University of North Texas and the Universidad de Chile, is Silander’s former graduate student at UConn.) More than 50 percent of liverwort and moss species are native to the temperate rainforests of southern South America. The authors of the new paper showed that more than 5 percent of the world’s bryophytes are found on less than .01 percent of the earth’s land surface at the southern tip of South America. The ecological role of mosses is not just of interest to biologists, Goffinet says. “Tourism with a hand lens” has become big business in Chile, where the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve protects mosses. On the island in the Cape Horn region where Goffinet has conducted field studies, eco-tourism has become so important to the local economy that “everyone wants to have a hostel.” And his field guide to mosses was published by the Chilean Ministry of Tourism. The lure of observing and recording species of mosses, many of which are documented in the books in Olson’s collection, continues to attract amateur naturalists as well as professional scientists. |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |

The collection is rivaled only by libraries in a handful of places, such as the New York Botanical Gardens.

The collection is rivaled only by libraries in a handful of places, such as the New York Botanical Gardens.