|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | GRANTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

Researchers make progress in areas of heart disease, muscle injury by Chris DeFrancesco - February 19, 2008 | ||||

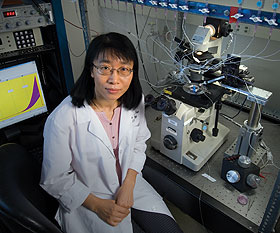

| Researchers at the UConn Health Center have identified a gene they believe plays a significant role in the development of heart disease. Lead investigator Lixia Yue, assistant professor of cell biology, says the TRPM7 gene provides a conduit that enables calcium to get into fibroblasts, a type of heart cell. Abnormal calcium levels in fibroblasts can lead to cardiac fibrosis. “Fibrosis often leads to a variety of cardiac diseases, including irregular heartbeat, enlarged heart, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death,” Yue says. “If you can control the calcium level, you can stop the fibrosis. Our focus is on the TRPM7 channel protein. The question now is, how do we moderate this channel to prevent fibrosis?” Yue, a faculty member in the Pat and Jim Calhoun Cardiology Center, presented her findings at an American Heart Association conference in Orlando, Fla., last fall. The study abstract was published in the American Heart Association journal Circulation. Yue’s team is now following up on this initial lead. “This work provided the first evidence of this channel’s existence in human cardiac tissue, and has yielded novel information that will give us a better understanding of how certain cardiac diseases can originate,” says Dr. Bruce Liang, director of the Calhoun Cardiology Center. Jianyang Du, Heun Soh, and Dr. David Silverman collaborated with Yue and Liang on the research. Liang also was the principal investigator on a study that found a possible key to reducing vulnerability to skeletal muscle injury, published in the December issue of the American Journal of Physiology – Heart and Circulatory Physiology. Liang led a team of scientists who have identified a specific receptor (adenosine A3) with protective qualities that decrease muscle injury in mice.

The Department of Defense provided funding for this research, with the objective of determining how to reduce muscle injuries in U.S military personnel. “Our soldiers suffer a high rate of skeletal muscle injury during the rapid-fire physical training, as well as during combat in adverse conditions, such as in a harsh climate or at high altitude,” Liang says. “Having a way to treat and reduce skeletal muscle injury in soldiers has the potential to be very beneficial.” The research team included Jingang Zheng, Dr. Ruibo Wang, and Dan Wu, from the Health Center, and researchers from the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine in Natick, Mass., and the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. “This work describes our novel findings on establishing a mouse model of skeletal muscle injury, and perhaps of equal importance, on a new therapeutic target to treat skeletal muscle injury,” Liang says. “Agents that stimulate adenosine A3 receptors represent an attractive therapeutic target because their use is not associated with any side effects, such as changes in heart rate or blood pressure. “Our work showed that administration of such agents in intact animals can bring about a significant reduction in the muscle injury without any apparent ill effect,” he adds. “Since there is no clinically effective drug that can reduce skeletal muscle injury, the work opens up a new area that could lead to better treatment for muscle injury.” |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |