|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | PTR | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

Colonialist’s marketing campaign created concept of New Englandby Elizabeth Omara-Otunnu - April 16, 2007 | ||||

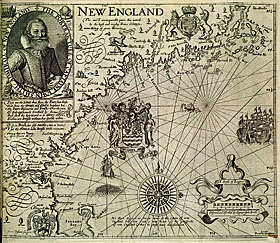

| The establishment of a place called New England in early colonial times resulted from a marketing campaign that was one of the earliest and most successful efforts at “place branding” ever undertaken, according to State Historian Walter Woodward. Woodward, an assistant professor of history and former advertising executive, recounted how New England’s identity evolved in the 17th century, thanks to the vision of Capt. John Smith and his tireless efforts to promote the region in hopes of securing capital for colonization and a leadership position for himself. Woodward spoke April 10 in Konover Auditorium; his talk was sponsored by the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. Place branding – the differentiation of a place so it appears to have desirable attributes – is currently a hot topic for diplomats, businesses, and tourism organizations, said Woodward, because a product’s place of origin has an impact on its perceived value. But it is not new. “Even without the specialized tools of the marketing industry, the techniques of today are projected back in time,” he said. In hopes of attracting venture capital to advance plantation schemes in northeast America, Smith sought to identify the region as a land of plenty. Woodward, who has analyzed the promotional materials Smith developed from 1615 through 1631, said Smith’s efforts reveal a highly competitive market for colonial investment in the early 1600’s. Smith faced a challenging task, he said. A plantation in Virginia was struggling, Smith’s own two previous voyages had failed, and an English colony established in 1607 had failed, its people returning home before the end of their first winter. Northeast America was seen as a cold, forbidding place. Smith set out to transform the image of the region, by re-casting it as New England. In 1616, he published a description based on a reconnoitering expedition the previous year. He distributed the materials and made presentations to key constituents and opinion leaders. Hoping to “loosen the purse strings of the avaricious and excite the adventurous,” Woodward said, “he packed his narrative with hyperbolic descriptions of the region’s health and fertility,” citing temperate air, pure water, and abundant game. Smith had first coined the term “New England” during his 1614 voyage. His “description gave full voice to this concept,” Woodward said. “He over-praised the benefits, and underplayed the challenges” in an effort to set this region apart from all other colonial venues, while making it seem comfortable and familiar. The idea of naming new territories after a foreign country was not new, but identifying it as a place with the same properties as the country of origin was novel, Woodward said. Maps were a crucial tool, said Woodward. Smith chose a top cartographer to produce a first-class map. “It’s easy for us to underestimate the power a map like that had in the 17th century, because we live in a media-saturated world,” Woodward added. “Both literate and non-literate people were very interested in colonization, and a visual of what the place was like could be immensely effective.” The map included an image of Smith with the title “Admiral of New England.”

“Proximity and similarity to England, safety, opportunity, destiny, and effective leadership were all designed into the cartographic image of New England … as part of Smith’s campaign to brand New England,” said Woodward. Smith then proceeded to “up the promotional ante – a technique that would later become a standard marketing ploy – with an endorsement,” said Woodward, encouraging the heir to the English throne to rename some of the locations shown on the map. He hoped to leverage this endorsement into financial support of others. Smith made the most of every opportunity. When Pocahontas, now married to a Virginia colonist, arrived in London, he sought to capitalize on his association with “the current hot ticket,” Woodward said. He wrote a book relating how Pocahontas had saved his life when he was in Virginia, and rushed books about New England into print so they were available within days of her arrival, distributing copies to highly placed people. After laying the groundwork with the nobility, Smith shifted his attention to the mercantile class, distributing books and maps to merchants. But his scheme never got off the ground. In 1620, with other settlement initiatives underway in Newfoundland and on the Hudson River, Smith launched a “media blitz” in London. He distributed thousands of copies of a brochure, appealing simultaneously to merchants and government officials by arguing that his project would serve both personal interests and the public good. It was “a textbook case of targeted direct marketing,” Woodward said, “involving face-to-face promotion with media saturation.” Ultimately, however, although his maps, books, and brand name were valued, Smith’s services were rejected. In November 1620, a merchant company received a new charter that officially named the American land between the 40th and 48th parallels of latitude New England. “In terms of place branding, this was a clear and permanent victory for Smith,” said Woodward. However, the charter gave no indication of support for Smith’s leadership. Smith wrote a number of popular books that “continued to beat the drum for New England,” but increasingly realized, Woodward said, that the colonization of New England would go on without him. In the decade after Smith’s death in 1631, thanks to significant migration from England, “New England managed to reproduce a more faithful replica of the home country than did any other colony,” said Woodward. “New England did indeed take on the character Smith had foreseen for it. … It became an American place associated with a distinctive set of geographical and cultural factors … and one of the most enduring of American place brands.” |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |