|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | PATENTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

Emeritus psychology professor was among first to study behavior geneticsby Cindy Weiss - April 24, 2006 |

||||

|

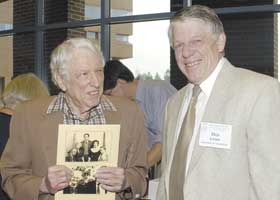

Benson Ginsburg’s long career will take another turn this summer, when the Behavior Genetics Association holds its 36th annual meeting at the Storrs campus. Ginsburg, 87, professor emeritus and a senior research professor of psychology, was one of the founders of the association. He hosted its first meeting at Storrs in 1971. Ginsburg still conducts research and has graduate students working at the UConn Health Center. His longevity as a researcher may be the legacy of his mentor, Professor Sewell Wright, a population geneticist and zoologist who was Ginsburg’s graduate advisor at the University of Chicago. Wright was still publishing at age 99. Or it may be in his genes. Ginsburg was among the first to study behavior genetics, and for 16 years, was head of the biobehavioral sciences department at Storrs, which he founded. Years before “multidisciplinary” became a byword in higher education, biobehavioral sciences was a department which reflected that approach to research, attracting faculty whose interests ranged from the biology of the brain and behavior to anthropology, neurobiology, and psychology. The department awarded more than 100 doctoral degrees, but has since been absorbed into psychology. Ginsburg still has a graduate student at the Health Center, Dr. Carlos Hernandez, an assistant professor of psychiatry, who is working toward the last behavior genetics degree that will be awarded at UConn. Relating behavior to genes is the essence of behavioral genetics, says psychology professor Stephen Maxson, who was also a student of Ginsburg’s. One of the great strengths of the field, he says, is that it does not attribute behavior strictly to genes or to environmental causes. “We need to understand how these two seemingly separate things relate to each other and interact,” Maxson says. Ginsburg’s research has been devoted to how they relate. He has studied fruit flies, mice, dogs, wolves, and humans. He once had a population of coy dogs – coyote-dog hybrids – housed on Horsebarn Hill for his research. The wolves he studied were kept there in an enclosed field with observation booths. Ginsburg was twice appointed a fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, and from 1946 through the 1980s, he was on the summer faculty of the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, known for genetic and cancer research. Charles Lowe, head of the psychology department, calls Ginsburg “a scholar and thinker who was decades ahead of his time.”

Ginsburg’s assertion in the 1950s that “it’s all in the genes, but it’s not 100 percent genetically determined” has become widely accepted only in the last decade, Lowe says. As the understanding of the human genome increases dramatically, says Lowe, Ginsburg’s work continues to have great relevance because of its emphasis on the interaction between genes and the environment. Before coming to UConn in 1968, Ginsburg was the William Rainey Harper Professor of Biology at the University of Chicago, a chair named after that university’s first president. He twice received the Quantrell Award at Chicago, the nation’s oldest prize for excellence in undergraduate teaching. Maxson was one of more than 23 Ph.D. students who studied with Ginsburg. He came to UConn in 1969 as an assistant professor, a year after his adviser. They have both studied aggression in mice. Both have been awarded the Dobzhansky Award by the Behavior Genetics Association, its senior award for outstanding research and accomplishments. Ginsburg received it in 1980 and Maxson in 1998. They are the only mentor and student combination to have received the award, Maxson says. “The more we learn about genes and genotypes, the more geneticists can see where commonalities are and where intervention is possible,” Ginsburg says. Behavioral genetics has influenced psychology and psychiatry with the recognition that many conditions are genetically based, he says. And, adds Maxson, how a gene affects behavior depends on what other genes are present and on environmental influences. When the 100 or so behavioral geneticists convene for their meeting in Storrs in June, they will reflect the changes in the field, which is growing and spawning new areas of interest, such as psychiatric genetics and anthropological genetics. Cloning presents a new area for study, says Ginsburg, enabling scientists to readily investigate how environmental differences affect the behavior of individuals with identical genetic make-ups. For more information about the Behavior Genetics Association meeting, go to http://www.conferences.uconn.edu/bga/. |

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |