|

| HOME | THIS ISSUE | CALENDAR | GRANTS | BACK ISSUES | < BACK | NEXT > |

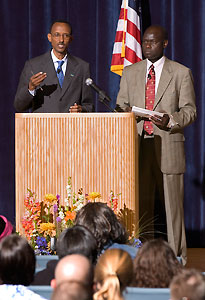

Rwandan president outlines human rights progress since ’94 genocideby Scott Brinckerhoff - September 26, 2005

|

||||

|

Eleven years after suffering the worst genocide the modern world has ever seen, the Republic of Rwanda is still “a work in progress.” But it has made great strides in restoring human rights and the rule of law, the country’s president said Sept. 19 during a packed forum at the Student Union Theatre. President Paul Kagame said outside observers who sometimes question his country’s rate of progress “fail to appreciate the context in which we operate,” a reference to the chaos following the ethnic conflict that took an estimated 800,000 lives in 100 days in 1994. As described by Kagame, the genocide left behind an emotionally traumatized population that included hundreds of thousands of widows, orphans, and refugees. The economy, the social structure, law and order, and the justice system were gone. Anarchy prevailed. Worse yet, the international community, which failed to act to stop the genocide, was again equally feckless as the nation began to pull itself together. Kagame, who spoke on “The Challenge of Human Rights in Rwanda After the 1994 Genocide,” was hosted by the UNESCO Chair and Institute of Comparative Human Rights. Kagame was part of a guerilla army that forced the Hutus from power after their genocidal war against the minority Tutsis. He was vice president of Rwanda’s transitional government from July 1994 to 2000, when he became president. He was elected to a full term in 2003. Today, he said, Rwanda has a constitution that guarantees minority party representation. The nation is secure, no longer under constant threat of random violence. The government has also established a system of justice that emphasizes correction more than punishment, recognizing that thousands who participated in the genocide will rejoin society. Outside investment is beginning to flow, and relations with the United States are “very good,” he said, despite the failure of the U.S. to intervene to stop the genocide. Kagame said people of different ethnic backgrounds live together in “near-total harmony,” encouraged to view themselves as Rwandans rather than members of a particular tribe. “There are no special groups,” he said. The president included several personal recollections that spoke to the depth of pain the genocide brought. He spoke of one individual who was among the many rape victims during the genocide and later gave birth to a child. Initially, the woman “wasn’t connecting well” to the child, Kagame said, but over time she came to appreciate the child as “the only immediate relative she has” following the genocide.

He also mentioned a man with whom he had spoken about the difficulty of burying hatred toward those who oppressed him. The man said, “Mr. President, I managed to live on and I tried to forgive because you asked us to do that.” In response to questions from the audience, Kagame made the following points:

|

| ADVANCE HOME UCONN HOME |