A Piece Of UConn History:

UConn’s Secret Society

|

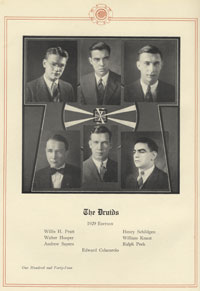

| The Druids were announced each year at the Junior Prom from the 1920’s to the 1940’s, and their names were published in the Nutmeg Yearbook. [Enlarge photo] |

|

Photo from the 1929 Nutmeg Yearbook |

Yale has its Skull and Bones, but secret societies are not limited to the Ivy League.

For decades, UConn had its Druids.

The Druids were an all-male (except for 1940) secret society that existed for 31 years. It was so secret that there are, except for annual entries in the Nutmeg yearbook, no extant records, meeting minutes, or other documentation of its activities.

From the yearbook entries, however, it’s clear that the influence of the small but powerful group was staggering. Nothing relating to student governance, it seems, was outside its purview.

“They were the classic secret men’s society,” says Daniel Blume, Class of 1953, and a member of the Archons, the group that replaced the Druids. “They were self-perpetuating, choosing their successors from campus leaders, like the president of the student government, editors of the Campus (the student newspaper), and guys in the fraternity system.”

The Druids “serve as a steering committee for the Student Senate, being the medium through which most of the legislation is introduced,” says the group’s entry in the 1939 yearbook.

“Their potent leadership controls and decides the progress and direction of all student activities of any importance,” according to 1940’s Nutmeg. That was also the year that the all-male barrier was broken, for one time only, with the selection for membership of Elizabeth Rourke, editor-in-chief of the 1939 yearbook.

According to the 1941 yearbook entry, selection and endorsement of an official school ring, new band uniforms, fire insurance for the personal effects of students living in dormitories, weekend movies, better faculty-student relations and better school spirit were all taken up by the Druids that year.

Membership was usually limited to six men, although it went as high as nine in 1928 and as low as four in 1935 and 1947. During World War II, participation was reduced to members not already called up for military service.

The existence of the group was revealed in a brief Connecticut Campus article published in May 1920. It reported that little information about the group “regarding its purpose, manner of organization or place of meeting can be published. However, there must be some sort of an organization, for new members will be ‘tapped’ today.” Exactly how the tapping worked is not now known, except that those selected were approached at the Junior Prom.

As the years passed, guessing who was a Druid must have been an active pastime for students. It also may have been a no-brainer; when the University had a student body numbering in the hundreds, leadership was a tight group of no more than two dozen or so. Exactly which editor, which president of a fraternity, and which team captain was a Druid was what kept the campus guessing.

How did they accomplish their mission? How and where did they hold their secret meetings? Was there a secret sign or a coded message that identified the Druids? We may never know, because meeting minutes and other records mysteriously disappeared shortly after the group was forced to go public in 1952.

With its membership depleted during the later years of World War II, the group saw its influence wane, and in the postwar years, some students failed to see the purpose of a secret organization.

Things began to fall apart in October 1951 when a motion went before the Student Senate to go on record “as being in favor of the Druids becoming an open organization.” That motion was defeated, but on Feb. 6, 1952, at “one of the most suspenseful meetings in many months,” reported the Campus, “the Student Senate … acted to force the Druids into the open. Prompted by the revelation of three senior senators who accused the Druids of being a secret society representing a threat to democratic student government, the Senate passed a motion to cease all recognition of ‘any organization, the membership and/or functions of which are secret.”

Charges of anti-Semitism and racism were leveled in the Student Senate against the Druids, although the three senators “were quick to point out that none of the present Druids were discriminatory or anti-Semitic ‘in any way.’”

During the course of the meeting, the Senate president, Peter Brodigan, revealed himself as a member of the Druids, as did senate member Paul Veillette, secretary of the secret group and one of the three senators working to expose it. He told the Campus that once initiated into the organization, he found he didn’t agree with its policies.

Over the next week, all the current Druids revealed themselves, breaking the three-decade tradition of secrecy. With their organization in shambles, the former Druids created a new men’s honor society, the Archons.

After receiving the official sanction of then-President Albert N. Jorgensen, the Archons swiftly replaced the Druids, with almost an identical membership, on March 25, 1952, as an open men’s honorary society. The new group, lacking the power and influence of its predecessors, lasted until 1970.

Over the 31 years that the Druids existed, 159 students were tapped as members. With two exceptions, all were white males – the exceptions were one woman and one Japanese American. At least three members, over the years, were Jewish. Druids were selected from the ranks of students leaders, so it is possible that as the diversity of the student body slowly changed, it became more likely that membership in the Druids reflected that change.

But we may never know.