For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page.

Tech Transfer Office Takes

Inventions From Lab To Industry

|

|

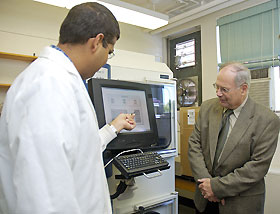

Michael Pikal, a professor of pharmaceutical sciences, right, reviews data with a graduate student. Pikal developed a formulation that extends the shelf-life of hemophilia medication and earned him a lucrative license. |

|

Photo by Melissa Arbo

|

The science behind the next big technological breakthrough may already have been developed at UConn. But is the research sitting unused on a shelf or in a filing cabinet or computer?

That is becoming increasingly unlikely since UConn began to aggressively push new technologies out of its labs and into commercial uses, a process commonly called “technology transfer.” Launching University research into the realm of patents, licenses, and corporate partnerships is intended to help expand the state’s innovation-based economy, as new businesses and new jobs are created around new ideas.

“I think we have made considerable progress in fostering commercialization of UConn technologies during the last four years,” says Michael Newborg, executive director of UConn’s Center for Science and Technology Commercialization (CSTC), which oversees technology transfer for the University, including the Health Center, Avery Point, and Stamford campuses.

When a researcher has invented a new technology, the first step in the process is to disclose the invention to an official of the institution. UConn faculty disclosed 53 new technologies in 2001; 72 in 2002; and 83 in 2003.

The technology is then evaluated for its commercial potential and suitability for patenting, by one of the CSTC’s four professionals. The CTSC then oversees the patenting process if appropriate. The next step is for the CSTC to market the technology to the relevant industrial sector and to facilitate the industry partner’s evaluation evaluation of it. If the technology meets the industry partner’s criteria, the CSTC will then negotiate a license, and ultimately will distribute the revenue from the license.

In 2003, UConn faculty received 21 patents, up from nine in 2001.

Additionally, since 2001, the CSTC has helped four faculty members start their own companies, and is helping two more to develop such companies, while 87 options and licenses were signed with existing companies.

“The CSTC currently receives approximately 75 new invention disclosures by faculty and oversees the filing of more than 50 U.S. patent applications each year,” Newborg says. “Ten to 15 commercial development agreements are completed annually; and licensing income has grown from $650,000 in 2000 to $1.7 million in 2004.”

The CSTC recently engineered its first million-dollar deal. The beneficiary is Michael Pikal, a pharmacy professor who in 1998, using research funding from the global healthcare giant Baxter International, successfully developed a blood-clotting formulation used to extend the shelf-life of a medication used by hemophilia patients.

Baxter filed a patent application on Pikal’s discovery in 2000, and a year later UConn licensed its rights to the patent to Baxter, giving the company exclusive right to the formulation in exchange for increasing annual licensing fees. In 2003, the medication Advate was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and placed on the market.

Then in fall 2003, UConn was approached by Drug Royalty Corp., a Canadian-based company whose assets consist primarily of an international portfolio of royalty interests in a variety of high-profile drugs. The company offered to purchase the income stream due UConn over time for a million-dollar lump-sum payment.

A deal was agreed upon earlier this year. Newborg says the money has been distributed to the co-inventors (Pikal had an associate who has since left the University), Pikal’s research account, his department chair, the dean of pharmacy, and the University.

“I’m very satisfied,” Pikal says. “It’s not often that we see immediate results from our research. The key here was that we developed a product that was worth something and had enormous economic potential to a corporation. But I do science; I’m not in the business of commercialization. Our tech transfer office did a tremendous job putting this deal together.”

The work of the CSTC, which is based at the Health Center in Farmington, is largely invisible but looms large for inventors seeking to commercialize their science and investors hoping to capitalize on it.

“A lot of this is sitting down and working out the details of business negotiations, which scientists are not used to,” says Newborg. “An investigator can’t just say, ‘What we’re discovering is obviously great stuff.’ There needs to be a bridge between the laboratory and the companies that will ultimately develop and commercialize these products. We’re here to create that bridge.”

The push to turn academic research into real-world applications has grown among universities since changes in the law gave them title to inventions stemming from federally funded research. The federal government subsidizes the majority of work done in university labs.

Over the past four years, Newborg and his colleagues have helped create at UConn what he calls a “one-stop, soup-to-nuts program” that offers faculty advice on patenting, licensing, forming a business, marketing the product, and obtaining legal services. There are three major components of the program:

- Licensing: some research can be spun off into a start-up company, but

most faculty inventions are best licensed to an existing company, Newborg

says.

- Start-Ups: the UConn Research & Development Corp. helps the University

start new companies by analyzing the market, helping with a business plan,

and identifying potential sources of investors.

- Incubators: the University’s Technology Incubation Program assists in the successful creation of entrepreneurial companies by providing space and services to start-up companies. Incubator space is available at the Storrs, Farmington, and Avery Point campuses.

Additionally, last month the state’s Department of Economic and Community Development agreed to provide $200,000 annually to the CSTC to help finance the building of prototypes or conducting of experiments to show that what has been discovered in the lab is commercially viable. Newborg anticipates that up to five prototype projects can be funded each year through the program.

“With this ability to fund the critical gap between a laboratory observation and a new business opportunity, with R&D to do spin outs, and our incubator space, we now have tech transfer at UConn that exceeds what is available at many universities,” says Newborg. “What we hope to see now are even more disclosures, especially in the life sciences.”

CSTC’s entrepreneurial emphasis is helping raise the profile of UConn and the state among the high-tech business community around the country. Last month, for example, a report issued by the Milken Institute, a respected, independent California-based economic think tank, ranked Connecticut third among the 50 states for its potential to capitalize on biotechnology and pharmaceutical growth over the next decade. Its rankings were based on a composite index of research funding, venture capital, workforce availability, and innovation. Milken researchers cited the state’s life-science industry, research institutions, and entrepreneurial sector as keys for new business formation.

Newborg recognizes that not every UConn researcher will become an entrepreneur, and that the primary mission of faculty is teaching and conducting basic research. But, he says, helping license technologies and form new companies is a way the University can put knowledge to work for the public good and create a revenue stream to fund further research.

“Our work is part of higher education’s service mission,” he says. “Much university research is financed with tax-payer dollars, and this is one way we can provide society some return on that investment.”