For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page.

Why Truth Matters Is Focus

Of Philosopher's New Book

Truth and truthfulness have been dominant themes in the 2004 presidential campaigns. Did Sen. John Kerry lie about the circumstances under which he received military commendations? Did President Bush tell the world that Iraq bought uranium from Niger, even when he knew that claim was false? And what to make of the debates in which the candidates accused each other of “not being straight” with the American people?

|

|

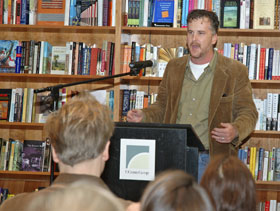

Michael Lynch, associate professor of philosophy and author of True to Life:

Why Truth Matters, speaks at the UConn Co-op during a book-signing event

earlier this month. |

Into this rhetorical perfect storm sails True to Life: Why Truth Matters, by Michael P. Lynch (MIT Press, 2004). Arguing that truth is objective and that we should care about it for its own sake – regardless of what is personally convenient or politically expedient – the book has brought philosophy to bear on issues of mainstream appeal and relevance. A Sept. 10 article about the book in The Chronicle of Higher Education prompted, among other spin-offs, a lengthy discussion about truth on the Internet, and Lynch has been interviewed by National Public Radio.

Lynch, who is new to the University this year and is the former chair of the philosophy department at Connecticut College, has been exploring the nature of truth for the past 10 years. His previous book is the 1998 monograph Truth in Context.

This new book, he says, arose out of the realization that many people in our culture are increasingly confused about what truth is, and cynical about its value. He felt motivated to understand why. “Why is it that, for instance, a reality TV show isn’t considered an oxymoron?” he says. “Why is it that we ended up going to war in Iraq, allegedly because we believed there were WMDs? That turns out to be false, and yet a lot of people don’t seem to really care about that.”

In True to Life, Lynch defends the very idea of objective truth. Cynical pragmatists have attacked the notion by claiming that what matters is not the actual truth but rather the consequences. For example, even if the president was not entirely truthful about his reasons for going to war, what matters is that many Americans believe that the world is better off with Saddam Hussein in jail.

Relativists have argued that the truth can be spun so many ways that it’s

naive and useless to commit to any one perspective. Meanwhile, at the opposite end

of the spectrum, dogmatists have invoked what they see as absolute truths (that,

for example, Western culture is superior to all

others) to oppress others.

Lynch argues that the truth may be very complex, and that there may even be more than one truth in a given situation, but somewhere between ironic detachment and self-righteous dogmatism exists a truth that ordinary people can pursue through the gathering and weighing of evidence.

“You think carefully, you pay attention, and you don’t accept things just because people say that they’re so,” he says. “Critical thinking leads you to the truth.”

Digging deeply into the details of a matter is not easy, Lynch acknowledges, especially when we are bombarded with information and opinion from the Internet, television, news-papers, and talk radio.

The truth is worth pursuing, however, in part because it is relevant to our personal happiness. Says Lynch, “Unless you care about truth, you’re not going to be able to live authentically, speak with integrity, or be sincere.” In other words, we must seek the truth in order to form opinions about what we care about and believe in, as these form the basis of how we act and how we live our lives.

What’s more, Lynch reasons, caring about the truth – in particular, the truthfulness of our government – is critical to democracy. In the Chronicle article, he states: “The less a government feels the need to be truthful, the more prone it is to try and get away with doing what wouldn’t be approved by its citizens in the light of day, whether that means breaking into the Watergate Hotel, bombing Cambodia, or authorizing the use of torture on prisoners. Even when they don’t affect us directly, secret actions like those indirectly damage the integrity of our democracy.”

Lynch recognizes that his use of examples from current politics may lead some critics to charge that he is putting forth a liberal agenda in an election season. “Which is unfortunate,” he says, “because the whole point of the book is that truth matters independently of its consequences. Truth matters for its own sake.”

He adds, “I’ve been working on this book for the past six years. It just so happens that it is coming out at the same time that this issue is of pressing importance to the nation.”