For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page.

Javidi's Holographic Imaging

Has Medical, Security Applications

Humans live in a three-dimensional world, but the images they view are almost entirely two-dimensional. That has been the case for as long as mankind has been displaying images, using everything from scratches on a cave wall to pixels on a computer screen.

|

|

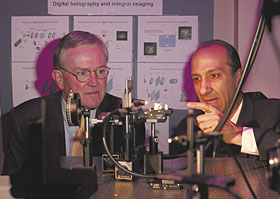

Bahram Javidi, Board of Trustees Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering,

right, discusses with President Philip E. Austin the new imaging technology he is

developing at his lab in the ITE Building. |

Bahram Javidi, Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, is deploying his extensive knowledge of optics and image processing to add that third dimension - depth - to a system that may prove valuable to homeland security, and medical and military applications.

Javidi's laser-based computational holographic imaging technique is not like the criss-crossing laser beam security system that Tom Cruise managed to defeat while ripping off a vault in Mission Impossible 2. Javidi's version is far more complex to visualize and understand, although it has at its heart a familiar human trait: 3-D vision.

"Three-dimensional imaging mimics human vision, and gives us vastly more data - and thus a far better picture - than two-dimensional does," Javidi says. "The holographic imaging system doesn't have the shortcomings of 2-D imaging using a camera. For example, a camera's focal length has to change as an object moves, losing focus, or the camera has to switch angles to simulate the 3-D effect."

3-D Images

Javidi's system uses a laser to acquire data in all three planes

of the object being "photographed." The data are processed by

a computer and the object is "reconstructed" and displayed as

a holographic 3-D image. The data itself can be stored and manipulated

like any other data.

In a homeland security scenario, Javidi's system might be used to zero in on a particular facial feature - say, the ears - of people as they enter a shopping mall, for example. Since ears are said to be as unique as fingerprints, the images could be compared with the ears of known terrorists immediately, enabling law enforcement to stop and question suspects without waiting for time-consuming processing to occur. By limiting the imagery to the ears, Javidi explains, the amount of data becomes much more manageable than if the entire face had to be reconstructed in 3-D.

Javidi says that although many lasers can harm humans, there are also safe lasers, as well as other sensors that could be used for this kind of application. But safety aside, he says there would surely be legal issues from a public that does not like the idea of being actively watched, much less by laser.

He adds that the system would face fewer hurdles in locations where an intruder was forewarned about the surveillance, such as the periphery of a military installation or a border between countries.

The system could also be used in medical applications, to give a 3-D view of an organ or tumor, for example. Or, in a military scenario, the laser would have to do no more than acquire an image of the barrel of a tank's gun for operators to know what kind of tank they were looking at.

Optical Storage

Holographic imaging is only a small part of what goes on in

Javidi's lab. His interests include many, if not all, of the

ways optical systems can serve humanity - from digital image

processing and pattern recognition to communication systems,

optical data storage, and signal processing.

"Optical systems use light to display information, process information, store and transmit it," Javidi says. "Optical systems are more powerful and secure than electronic ones." He adds that their complexity, compared to a binary computer system, allows for endless variations that enhance security by manipulating such characteristics as polarization, phase, and wavelengths. Photography, CD's, and DVD's are all examples of optical storage systems.

Another familiar example is the driver's license, with its holographic image that can be used to store all manner of encoded biometric and other information.

Recently, Javidi co-authored a paper describing how vast amounts of data could be transmitted by hologram over fiber-optic lines, optically encrypted to provide the highest possible degree of security. "After transmission, remote users in possession of the key can decrypt the data," he explains.

A Range of Applications

Javidi often conducts short courses in his specialties for

industrial audiences around the world. His reputation is such

that colleagues recognize his name instantly, says his department

head, Robert Magnusson:

"He's literally world-famous in his areas of expertise - optical imaging, 3-D imaging, and display and related disciplines," Magnusson says. "Sometimes I'll meet someone new at a conference and they'll say, 'UConn? Isn't that where Bahram Javidi is from?'"

Magnusson adds that Javidi's students also hold him in high regard, giving him enthusiastic reviews after completing a course with him. "He's an excellent educator who is very creative and has high standards," Magnusson says.

Javidi's reputation has helped him win a wide range of grants, from groups as varied as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency to the Connecticut Department of Transportation, for which he described a system for automatically detecting road surface degradations. Another optically based system designed by Javidi can be used to inspect roads quickly from a vehicle for signs of damage or degradation. He has also been funded by Korean agencies for his work on 3-D TV and displays.

A graduate of George Washington University, with advanced degrees in electrical engineering from Penn State, Javidi sees optical technology conferring security benefits to mankind amid an ongoing debate about whether such technology intrudes too much on privacy.

But one benefit, he predicts, will not stir controversy - 3-D television and movies. Unlike the 3-D movies of the 1950's, with lions leaping off the screen into an audience wearing funny-looking glasses, the upcoming technology won't need the glasses and the images will be frighteningly real. That is, Javidi says, if the technology can be deployed with an affordable price tag.