For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page.

NSF Official Offers Grad Students

Tips On Writing Grant Proposals

Writing a successful grant proposal depends not only on being creative in developing a project, but also on having the ability to follow directions, according to a National Science Foundation official.

|

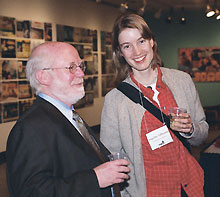

Kelman Wieder, program director for ecosystem studies at the NSF, speaks with Angeline Tillmanns, a doctoral student at the Unliversity of Ottawa, after his presenation on applying for research funding.

Photo by Jordan Bender

|

Kelman Wieder offered tips for doing both to students attending the 2nd Northeast Ecology and Evolution Conference, which was held at UConn this year. Wieder, a professor of biology at Villanova University who is currently program director for ecosystem studies at the NSF, spoke at the Wilbur Cross Reading Room March 26, as part of the two-day conference.

Wieder advised students to be open to different types of intellectual stimulus: "When you're least expecting it - when you're cutting the grass, taking a walk, or you're in a bar - you may see something that the artistic side of your brain picks up on. Then let the two sides of your brain connect. That's when things happen."

Wieder said the NSF has two criteria for evaluating every proposal: intellectual merit, which he called 'the sine qua non' of a successful proposal, and awareness of the broader context.

For a proposal to be funded, said Wieder, "you need to know your own work inside and out," and be able to cite the major papers in the field in recent years.

"Be excited about your own research," he urged the students, "and learn how to express that orally and in writing."

Having identified a relevant funding source, "identify how your research fits into the targeted program — and follow the guidelines," Wieder said. "You have to be able to follow directions in any kind of research. If you can't, why should anyone give you money for research?"

Wieder said the National Science Foundation was established in the aftermath of World War II, when presidential scientific advisor, Vannevar Bush, recommended the creation of a national research foundation. The foundation was envisaged as a mechanism for adapting the country's war- time science program, which had included the development of nuclear weapons, to conditions of peace.

When the NSF was founded in 1950, said Wieder, its entire budget was $225,000. Now its budget amounts to about $5 billion.

Funding research by students is a high priority for the NSF and other agencies, he said: "Most of the hands-on research is done by students and post-docs, hence the need for continuous investment in student research at all levels."

He said the creativity that is needed for good science relies on first having the knowledge to identify what is 'new.' Another necessary ingredient is intellectual curiosity. "Retain a questioning mind," he said. "Remember that once upon a time, the world was flat." Without some skeptics, he added, that view might still prevail.

Good science also calls for "passion, coupled with optimism;" "discussion, undertaken with respect;" and "the willingness to embark on risky endeavors" while striking a balance between the likely payoff and the time or effort required to attain it. "You want to be in on the action," Wieder said.

A good researcher must be highly familiar with his or her own work, he said. "You should be able to explain your work to anyone in a few clear, cogent sentences, for example, if you're sitting on an airplane and someone asks what you do."

Presentation is important, he said.

"Like it or not, there's a Zen to proposal writing," Wieder said. "Whatever the format, the page should have a certain amount of physical appeal. Impressions matter." In the 21st century, he added, there is no excuse for spelling and typographical errors: "They annoy reviewers."

Wieder said persistence helps. Although he has had continuous research funding for 20 years, more of his proposals have been rejected than accepted. At many agencies, including NSF, resubmissions fare better, he said.

"If your proposal is reasonably received but not funded," he said, "make changes and resubmit it."

The conference, which was organized by graduate students in ecology and evolutionary biology, was attended by more than 210 people, including 60 from UConn.

Hosting the conference was an opportunity for graduate students to learn the "business of science," as well as a time to begin creating professional colleagues, said Janet Greger, vice provost for research and graduate education and dean of the Graduate School.

"Look around the room," she said. "You will still be meeting these people for the next 30 years."