|

This is an archived article.

For the latest news, go to the Advance Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. |

||||

|

Son Of UConn's First Black Basketball

"My experience at UConn was very pleasant," says Harrison Brooks Fitch Jr., '64. "There were challenges, but they were very small. There were a few incidents, but nothing like what my father faced."

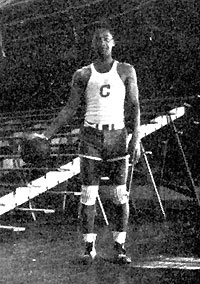

Fitch's father, Harrison "Honey" Fitch, who attended UConn in the mid-1930s, was the first African American to play basketball for what was then known as Connecticut State College. Fitch entered the college as a freshman in 1932, having been a standout player at his high school in New Haven. But in his sophomore year he endured racial discrimination from an opposing team that was ultimately a contributing factor in his leaving the college. Seventy years ago, Fitch was at the center of a racial incident regarding a basketball game at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London. On Jan. 28, 1934, just before game time, Coast Guard officials entered a protest against Fitch, arguing that because half of the Academy's student body was from southern states, they had a tradition "that no negro players be permitted to engage in contests at the Academy." In their own protest, Fitch's teammates threatened to leave the basketball court if he was not allowed to play. They joined him in warming up, shooting, and passing to get ready. Meanwhile, officials for both schools argued, delaying the start of the game for several hours. Coast Guard relented, and the game was played. Connecticut won, 31 to 29. But Harrison Fitch did not see a minute of court time. John Heldman, CSC's head coach, kept him on the bench, and never explained why. Heldman was already under fire from students and alumni, after compiling a record of only losing seasons since he began as coach in 1931. He would hold on for another year, but resigned after losing the first two games - one to the alumni team - in the 1935-36 season. Writing in the Feb. 13, 1934 issue of the Connecticut Campus, sports editor Jules Pinsky said, "In every (basketball) contest in which Fitch played, there were unpleasant references to Fitch's (skin) color." Out of 14 rivals, only Brown University and the University of New Hampshire were cited by Pinsky as not participating in using racial epithets against Fitch. Following the Coast Guard game, Roy Guyer, CSC's athletic director, and his counterpart at Coast Guard issued a joint statement indicating that the relationship between the two schools "was not impaired and that in the future any student would be eligible to participate in athletic events" between them. Fitch left CSC at the end of the academic term, transferring to American International College in Springfield, Mass. After earning his degree, he worked in research for Monsanto Corp. He married Hazel Brandrum in 1939, and they had two sons: Harrison Brooks and Charles. An article about Harrison Fitch Sr. appeared in the Advance six years ago. Charles Fitch came across it recently on the Internet, and sent a copy to Brooks. When he read in the Feb. 9, 1998 Advance article that "it is not known what happened to Fitch" after he left UConn, Brooks called the editor. Brooks Fitch says his father never talked about the Coast Guard incident, but he did indicate over the years that he had a good experience at CSC, and enjoyed his relationship with other members of the basketball team. His transfer to American International was due to financial constraints, as well as the racial incident in New London. Over the years, his father remained a fan of Connecticut basketball, and watched men's and women's games on television up until he died in the early 1990's. Brooks Fitch, now living in Dallas, says he visits the Storrs campus whenever he gets the chance. And whenever the opportunity arises, he says, he encourages African American students to apply to the University. |