|

This is an archived article.

For the latest news, go to the

Advance Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. | ||||||

|

Marine Science Team Explores Picture a mountain chain - New Hampshire's White Mountains, for example - one majestic peak after another, separated by valleys. Now envision a similar chain underwater, its peaks covered by 4,700 feet of ocean. There's just such a chain off the east coast of the United States, extending from Georges Bank, 75 miles offshore, to northeast of Bermuda. The 35 or so underwater mountains in the chain, that have names like Muir and Gregg, are known as the New England seamounts and they are the latest major exploration site for the National Undersea Research Center at UConn. University researchers Peter Auster and Ivar Babb were among the two dozen scientists and educators from a variety of institutions who participated in the ocean exploration project, which was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Seamounts, because of their isolation, are home to many species found nowhere else. The mission plan called for dives on three seamounts - Manning, Kelvin and Bear - to survey patterns in the distribution of biological diversity. In particular, the mission focused on deep sea corals, fishes, and invertebrates. Auster, science director of the National Undersea Research Center and a fish ecologist, was not merely looking for new species. "The deep ocean is the largest living habitat in our planet, and we know relatively little about it," he says. "We don't know much about who and where the players are within the underwater landscape, and before we can ask reasonably intelligent research questions, this type of exploratory science is needed." By studying the seamounts before human impact occurs, Auster hopes to gain a better understanding of how individual organisms interact with their environment, while also documenting them with photos and video. His work in the area of fish habitat conservation has earned him a national reputation and a prestigious Pew Fellowship.

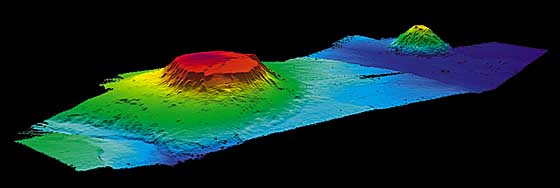

"Humans have stressed and exploited many fish populations throughout the world. If fishing expands to the seamounts, which seems inevitable," laments Auster, "we need to take some conservation action before significant damage is done." To observe and collect specimens on the seamounts, the team relied on the capabilities of a small research submersible called Alvin, made famous by its use in the discovery of the wreck of the Titanic. It is capable of carrying a pilot and two observers to nearly 14,000 feet, or two-and-a-half miles, below the water's surface. One of Auster's most memorable experiences during the trip was as the sub dropped down through the water column with the lights off. "It was like the Aurora Borealis show of lights," he says. About 800 meters (half a mile) under the surface, it was dark enough to see animals that glow in the dark, like jellyfish. At 1,800 meters, he recalls, "It's was a cool experience to be sitting there eating a peanut butter sandwich for lunch and watching wildlife that people never get a chance to see." The group collected as many samples as humanly possible to process, says Babb, director of the National Undersea Research Center, who described the mission as a "slam dunk". "We got every dive in and no equipment failed. The content was rich, the data we collected was outstanding, and it is now in the process of being analyzed," he says. Some of the specimens are being provided to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and the Peabody Museum at Yale University. The rare sights during the six dives included a couple of new deep sea coral species; unusual behavior by a species of sea star; and several species of fish outside the range of their usual habitats. Specific details are being held for scientific publication. Although this was the second time a manned submersible had explored Manning and Bear Seamounts, it was the very first visual exploration of Kelvin. Babb was one of just six people during this mission who eyeballed Kelvin through Alvin's porthole. During Babb's dive, Alvin reached a depth of about 2,000 meters, or about one-and-a-half miles, and then propelled up the steep mountainside. "We could see evidence of what was once an active volcano," Babb says. "Pillows of black lava formed the steep wall, and pink and red corals dotted the slope. At the top, we encountered a sandy plateau. Kelvin turned out to be a huge flat-top mountain." Babb, who handled the operational logistics during the mission, was responsible for coordinating the multibeam sonar, technology used to create three-dimensional maps of each seamount's features. He also worked closely with several marine educators invited to take part in the mission, including Diana Payne from the Connecticut Sea Grant program at UConn. The educators crafted daily web logs for a NOAA web site, as well as lesson plans for use with classes in grades 5 through 12. Babb and Payne coordinated a special experience for Southington High School students, that involved a live phone interview with Auster and the Alvin pilot while they were 1,600 meters (one mile) below the surface, using the submersible's underwater communication system. It will take many more trips to accurately characterize just a small portion of the seamount chain. Babb and Auster are anticipating continued support from NOAA's Office of Ocean Exploration, including funding for another trip to the seamounts next summer. | ||||||