|

This is an archived article.

For the latest news, go to the Advance Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. |

||

|

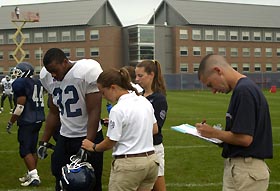

Athletes Help Researchers Study With a swig of water and a capsule nearly the size of a horse pill, 15 UConn football players became human subjects in a research project aimed at preventing injury and saving lives.

The departments of kinesiology and athletics teamed up for the NCAA-funded heat acclimatization study, conducted this summer during the first eight days of pre-season practice. The intercollegiate athletic regulatory agency wanted to find out how its new practice guidelines were affecting players. UConn was one of only two institutions chosen for the study, due in large part, to the reputation of the kinesiology department's Human Performance Laboratory, which is the site of a vast number of studies on heat, hydration, and exercise. Professor Larry Armstrong and Douglas Casa, an assistant professor, two of the lab's primary investigators, sought the expertise and participation of Dr. Jeffrey Anderson, director of sports medicine, and Bob Howard, the football team's head athletic trainer. They, in turn, received the full support of head football coach Randy Edsall. The collaboration between scientists and athletic personnel resulted in unprecedented research, says Casa. "This is one of the first times researchers were on the field during the first days of practice, gathering data on the heat and hydration status of football players to determine how practicing in the hot weather affects them," he says. For Edsall, it was all about helping athletes in terms of performance and safety. "If what we did here, in any small way, can help cut down on the number of tragedies that have occurred on the field around the country the past few years, then we've done something to help the game of football at all levels, and every second of the study was worthwhile," he says. "This will also help us as coaches learn just how far we can push our student-athletes during camp, and help prevent fatigue-related injuries in addition to heat stroke." Armstrong, who recently edited and coauthored a book on exertional heat illnesses, says the data they collected will show which positions on a football team are most at risk for developing heat illnesses and which drills affect players adversely. The same study was conducted this summer at West Chester University in Pennsylvania, a Division II school. It used to be that during the first day on the practice field, under the blazing August sun, collegiate football players suited up in all their equipment. However, the NCAA put new football practice rules into effect this summer. The changes were initiated by an increase in the number of heat-related deaths of football players. According to the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injuries, 13 occurred in the 1980s, 15 in the 1990s, and seven between 2000 and 2002. Coincidentally, as the UConn study began, heat illness made headlines on sports pages across the country after three Jacksonville Jaguar players in the National Football League suffered heat-related injuries. Under the new NCAA guidelines, football players are allowed to wear only their helmets on the first day of practice and gradually add equipment over the next four days. Instead of the rigorous two-a-day practices from the start, teams now practice just once a day until the sixth and eighth days, when a double dose is allowed. Two-a-day practices on consecutive days are forbidden. Armstrong, Casa, and their graduate students closely monitored the participating players during practice. Five players from each of three body types had been chosen, including the big, bulky offensive and defensive linemen; the leaner, faster wide receivers and defensive backs; and the muscular, but quick linebackers and running backs. Each day, the test subjects swallowed an encapsulated sensor, which emitted a low frequency radio wave. The technology was developed nearly 15 years ago for NASA to monitor astronauts during space flight. During the 24 or so hours it took to wend its way through the digestive system, a thermometer inside the capsule registered each player's core body temperature. While standing near the players, Casa and Armstrong used a recording device the size of a Palm Pilot to pick up the radio waves and keep track of all 15 pills at the same time. The researchers also collected heart rate measurements by taking each player's pulse at several points during practice. Urine samples gathered before and after practice were used to determine if the test subjects were well hydrated. Body weight measured before and after practice indicated the amount of fluid that had been lost. All fluid and food consumed during the study was recorded and analyzed by a registered dietitian. Test subjects were asked a serious of questions each day to measure their perception of thirst and how hot or cold they were feeling. Previous studies on the topic have been conducted in laboratories, but according to Casa, conditions of a real practice session cannot be mimicked in a laboratory setting. "We consider ourselves lucky to have proactive thinkers in the UConn athletics department enabling us to get the work done. There are not many universities where you would find the kind of support we received from the coach, his team, and the department," he says. Within the next couple of months, Armstrong and Casa will be submitting a report to the NCAA, and they will present their findings at the American College of Sports Medicine's annual meeting next June. |