|

This is an archived article. For

the latest news, go to the Advance Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. |

||

|

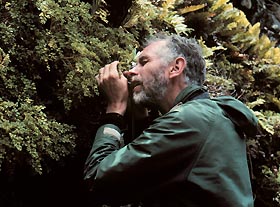

Anderson Goes The Extra Mile

Spicebushes are native plants and the first to flower in the spring, explains Anderson, who has been studying them for 25 years.

At another time, Anderson, professor and head of the ecology and evolutionary biology department, might be on a remote Chilean island rescuing biological treasures, or in the mountains of Guatemala looking for plants. His lab, on the first floor of the Torrey Life Sciences building, is peppered with baskets and other items made from plant fibers. Each is there for a reason. The stack of grass placemats on the counter, for example, is used when Anderson teaches a course about the ways in which plants have influenced the development of human civilization. "It's the most fun course that I teach," he says, "because I can talk about anything and everything." A nearby dish holds a bunch of sticks, also used in the course. "They're used for cleaning your teeth," he says. "They have some antibiotic properties." A long, braided cylindrical basket made of palm bark leans on a wall. "It's a Tipiti from Colombia," Anderson says. He stretches the flexible basket and demonstrates how it is used. "It extracts the bitter alkaloids from tapioca," he says. Anderson, who joined the University faculty in 1973, has been head of the department of ecology and evolutionary biology since 1990. In addition to overseeing a department of 30, he conducts his own research, teaches undergraduate and graduate courses, mentors graduate students, is on scores of University committees, and is involved with many professional organizations. "I like the diversity of my job," he says.

National Recognition Richard T. O'Grady, executive director of AIBS, describes Anderson is a "champion of integrative and organismal biology." The honor, presented at the AIBS annual meeting last month, consists of a plaque and lifetime membership in AIBS, an umbrella organization for 85 professional scientific societies and organizations in the biological sciences. Anderson served as president of the organization in 1999 and organized the first AIBS Presidents' Summit, which brought about an unprecedented increase in member societies. The combined membership of those societies is now 250,000, making AIBS the country's largest scientific organization. He says he has been "very happy to be involved with AIBS and particularly gratified with this award, because I worked very hard to help it focus on its umbrella role and to build the membership. At the first summit of presidents of the societies, we made tremendous progress. We discussed how we could be more effective if we gave up some of our individuality and worked together as a major organization." Anderson has been president of the Botanical Society of America (BSA), the American Society of Plant Taxonomists, and the Society for Economic Botany (SEB). He was on the Board of the Council of Scientific Society Presidents, and has been secretary of the Organization for Tropical Studies. Other honors include "best paper" awards from the American Society of Plant Taxonomists and SEB; a Merit Award from the BSA; the distinguished Biology Alumnus award from St. Cloud State University; and a Faculty Mentor of the Year award from the Compact for Faculty Diversity Institute for Teaching and Mentoring. He also received a Distinguished Alumni Professor award from the UConn Alumni Association in recognition of his teaching and his scholarly reputation.

Living Out Beliefs "I feel that we should all make contributions to those things that we believe in," he says. "I believe in the mission of bringing professional scientists together and promoting their messages of the importance of basic research, of science in education and to the development of our country. I also believe very strongly in the mission of public universities and public research-based universities in particular. I'm committed to making the department and University all that they can be." Anderson, who teaches both at the undergraduate and graduate levels, enjoys his role as teacher and mentor. "I like the formal classroom, where I teach introductory biology and graduate level courses," he says. "I enjoy the fresh enthusiasm that you get from first-year students, and the depth that you can take ideas and concepts to with graduate students. I like mentoring them and helping them develop their projects." Tom Philbrick, one of Anderson's former doctoral students and now a professor of biology at Western Connecticut State University, describes him as an "excellent role model. He is intense about learning and invests a lot of emotional energy and time with his students." Adds Philbrick, "He continues to be my advisor."

Long-Term Research A research project that he is particularly happy about these days involves the Pepino, a fruit native to the Andes in South America. For 25 years, Anderson and his students have been doing field work, greenhouse work, breeding, and chromosome and DNA studies to determine what might be the ancestor of the Pepino. "There is no known species associated with its origin," he says. Now, a colleague from Spain is trying to use Anderson's collected plants and information to improve the crop. He wants to enhance the taste by transferring some genes from the wild species to make a sweeter Pepino. "I can't tell you how excited I am," Anderson says. "It's gratifying in many ways because all of this basic science we do, which is really important, is now going find direct applications in agriculture, too." |

n a sunny spring

morning, Gregory Anderson and several students have

just returned from examining spicebushes in Mansfield.

n a sunny spring

morning, Gregory Anderson and several students have

just returned from examining spicebushes in Mansfield.