|

This is an archived article.

For the latest news, go to the Advance

Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. |

||

|

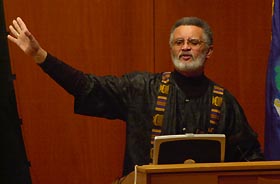

Historian Traces Roots Of

Western Civilization To Africa By Elizabeth Omara-Otunnu Black History Month should be called African History Month or World History Month, according to Ashra Kwesi, a Dallas-based historian and lecturer on ancient civilization. Despite the prevailing Eurocentric view of the world, without Africa and its people there would be no civilization, Kwesi said - not even the human race. Kwesi spoke Feb. 5 in Konover Auditorium, during a presentation sponsored by the African American Cultural Center as part of Black History Month.

He said the earliest human beings lived in Africa and fanned out across the globe from what he called the Fallopian tube of the Nile Valley. African Identity

Kwesi said it was the Leakeys, a family of white paleontologists, who presented the evidence to the world that Africans were the first human beings. Yet without his African assistant, Richard Leakey would never have found many of the relevant sites, Kwesi argued. Pointing to a slide depicting a series of increasingly humanoid figures intended to illustrate the evolution of early human beings, Kwesi noted that the artist portrayed the figures getting lighter skinned and more European-looking over time. "The more pigmentation they have, the more ape-like they are," he said. Kwesi said it was early Africans in predynastic Egypt who developed astrology and cosmology, and were the first to conceive of a monotheistic god. He showed slide after slide of Egyptian art and sculpture to support the view that the ancient Egyptians were black people, not - as some have argued - stylized representations of white people. He said many Westerners have gone to great lengths to conceal the African identity of the Egyptians. "There's no one prototype of African facial characteristics, but the [statues] with wide noses and thick lips they're systematically hiding and destroying." he said. He showed a slide of a newspaper clip reporting that scientists and special effects people had recreated a representation of the Egyptian King Tutankhamun from his mummified remains, and demonstrated that he was African. Another slide of a newspaper article illustrated the absurdity of some of the arguments to suggest that prominent ancient Egyptians were not black: "he was negroid but not actually Negro," read the article. Kwesi said an ancient Egyptian named Imhotep, during the third dynasty, was a physician who lived 2,000 years before Hippocrates, the Greek who is generally credited as the first doctor. He also built the first pyramid in stone. "Imhotep was a genius," Kwesi said, yet a sculptural representation of him had its "head knocked off because of hatred of the history of Africa." Borrowed Symbols

Kwesi asserted that the avenues that intersect the street grid in Washington, D.C., at diagonal angles from the Capitol, were based on the compass and plumb line, tools that were used in the construction of the Egyptian pyramids, "the greatest structures on earth." And he noted that the Washington Monument is the world's largest imitation of an Egyptian obelisk. "America's founding fathers saw themselves as inheritors of the Egyptian tradition," he said. Looking to the Future

"I see more Europeans on the African continent than Africans from America going to Africa," he said. "Our thinking has been within a European circumference," he added. "We have got to make a transition for the future." |