|

This is an archived article.

For the latest news, go to the Advance

Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. |

||

|

Speaker

Offers Guidelines For

Responsible Whistle Blowing By Richard Veilleux When university professors are caught crossing the line in their writings or research, violating local or federal ethical standards, the results can be disastrous. But they may not be alone: unless proper care is taken, the student or faculty member who reports those abuses also can be dragged down, according to a nationally known research ethicist.

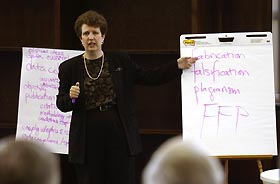

Tina Gunsalas, special counsel in the Office of University Counsel and an adjunct professor in the College of Law at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, walked about 150 students and faculty through the potential minefield they face, if they're ever unfortunate enough to discover ethical abuses by a colleague. She made her remarks during a lecture Oct. 17 in the newly renovated North Reading Room of the Wilbur Cross Building. Whistle blowing at a university, she said, can end a career. Nonetheless, said Gunsalas, one of the top research ethicists in the nation, students and professors who remain silent when they think a colleague is violating ethical mores "is doing a disservice to their university, their profession, and their colleagues by staying silent. "It's a touchy topic," she said. "It's not a topic people like to think about, that people like to talk about. A lot of people won't come forward with concerns because they're uncomfortable or not sure of themselves. A lot of times, they don't know how to raise their concerns." Sometimes, she said, people are afraid of the repercussions. Yet, although caution should be the watchword when reporting ethical violations, whistle blowing can be done without ending a professional career. "Part of it is being sure that you are being professional," she said. "Be certain you have your facts, your data. Know what your goal is. Is it co-authorship of a research paper? Having someone admit an error? Bringing someone up on charges? "There are rules we don't often talk about, but they're particularly important to follow if you're at the bottom of the power curve," she said. "For students, that means broaching the subject with someone higher on the chain than the person you're concerned about - a department head, dean, or veteran faculty member - leveling the playing field." Gunsalas offered six rules for responsible whistle blowing.

Gunsalas adds that disputes don't happen often. During her eight-year tenure as research standards officer at the University of Illinois, she said she averaged two to five inquiries a year, and no more than five of those resulted in an investigation. Of all her cases, she said, there were only two findings of misconduct. An article Gunsalas wrote on the topic for the journal Science and Engineering Ethics is available through the Graduate School. Video copies of her talk also are available on loan. |