|

This is an archived article.

For the latest news, go to the Advance

Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. |

||

|

Indian

Law a Burgeoning Field for Law School

By Allison Thompson Soon after the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs announced its decision this summer to recognize a Connecticut-based Indian tribe, calls began pouring into the UConn School of Law from people seeking help in deciphering the ruling. It was the latest indication that UConn is becoming an important source for understanding Indian law. "With Indian law issues surfacing in more and more legal arenas, we must ensure that our students are well versed in the topic," says Nell Newton, dean of the law school. "As the state school, it is vitally important that the School of Law serve as a source of impartial and accurate information about the role of Indian tribes in Connecticut and in the United States legal system."

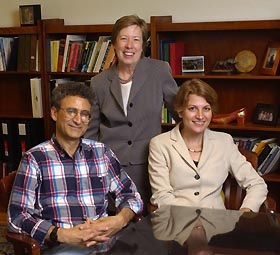

When Newton arrived at the law school two years ago, she said she wanted to create the foremost Indian law program in the Northeast. Already she's well on her way to achieving that goal. "Nell's presence has inspired those of us on the faculty who have had interests in areas that were relevant to Indian law to delve into the topic," says Richard Pomp, a professor at the law school who specializes in tax law, and writes and teaches on Indian law. "Her arrival has provided the faculty and students with both an intellectual and an institutional leader in this area." After spending more than 25 years studying Indian law, Newton is considered one of the nation's premier authorities on the topic. She is managing editor of the current revision of the Handbook of Indian Law, the book that lawyers, judges and scholars turn to when searching for information about the topic. Through her work and that of other faculty members, as well as a new Indian law class, Newton hopes to expose law school students to a subject they are sure to encounter in their professional lives. "Increasingly, attorneys in general practice may encounter Indian law, and it is important to be prepared," she says. "Connecticut only has two federally recognized Indian tribes, but because our state is small and the tribes operate large enterprises, Indian legal issues arise increasingly. It is a shame when an attorney learns about tribal court only when his or her client is served with papers to appear in tribal court, which is the forum of choice for many kinds of issues." Since 1998, the law school has offered a popular introductory course on Indian law. Originally taught by Professor Colin Tait, the class is now taught by Bethany Berger, a research professor specializing in Indian law who joined the faculty partly out of a desire to work with Newton. "A very common reaction to the course material is sadness at the history of promises broken and legal rules bent concerning the treatment of Indians and tribes, often combined with admiration that tribes have continued to exist despite this history," Berger says. "I hope the students also get a sense of what the survival of core principles of tribal sovereignty means for the rule of law in America. In a legal system that often focuses on individual rights, I think that the course also challenges students to think about group rights, and why and whether they should be protected." Next semester, Berger and Pomp will begin teaching the school's second Indian law class, which will focus on taxation and Indian law. Only a few other law schools, most of them in the West, offer two or more Indian law courses. "During my three years of law school, an Indian law course was offered only once and it was taught by two adjunct faculty members," says Berger, who graduated from Yale Law School. By contrast, she adds, Indian law has long been taught at UConn on a regular basis by full-time faculty members. In addition to preparing for the new Indian law class, Pomp, who previously drafted some tax laws for the Navajo Nation, is also writing a textbook on the taxation of American Indians, thought to be the first of its kind. "With all the renewed interest in Indian economic affairs, sparked by concerns over the spread of casinos and the increase in applications for federal recognition by various groups, this is an ideal time for a systematic study of the powers the federal government, the states, and the Indians have to tax economic activities occurring on and off reservations, and the immunities the tribes have from state and federal taxation," Pomp notes. Law school alumni are well represented in Indian law, with graduates working on behalf of tribes and in the state Attorney General's office. Notable graduates include Jackson King, Class of '68, who was instrumental in settling land claims between the Mashantucket Pequot tribe and local towns, and Lewis Rome, Class of '57, whose law firm represents the Mohegan tribe as outside counsel. In the future, Newton hopes to create an Indian law clinic that would allow students to work with tribal governments. She would eventually also like to open the first academic center focusing on the special legal issues of tribes in the original 13 states, and concentrate on helping newly recognized tribes develop governmental institutions, such as court systems. |