|

This is an archived article.

For the latest news, go to the Advance

Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. |

||||

|

UConn

Experts, Equipment Help

Locate 19th Century Shipwreck By Janice Palmer

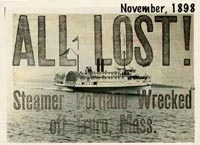

The wreck of the steamship Portland has been located off the Massachusetts coast in the 842-square-mile Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, between Cape Cod and Cape Ann. Its exact whereabouts are being kept secret to protect it from scavengers.

The Portland, a 291-foot side-wheel paddleboat, sank on the evening of Nov. 26, 1898, with nearly 200 passengers and crew onboard. It had sailed from Boston Harbor at 7 p.m. and was heading to Portland, Me., even though a storm was predicted for the area and snow had begun to fall. The storm turned out to be the gale of the century, when two powerful weather fronts collided. Hundreds of homes and boats in the region were destroyed and more than 500 people died. Since then there have been questions about where the Portland went down, what caused it to sink, and why the captain ignored weather reports. In June of this year, Ivar Babb, director of the National Undersea Research Center at Avery Point, received a phone call from the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, requesting help in locating the wreck. Earlier work by the Sanctuary, two underwater explorers, and the U.S.Geological Survey had zeroed in on the ship's approximate location, but better technology was needed to actually identify the remaining ruins. The Sanctuary asked if the Center would conduct side-scan sonar, but Babb told them he would do them one better. "Since our ship, the R/V Connecticut was going to be in the sanctuary for our Aquanauts Program, we offered to provide the vessel and one of our remotely operated vehicles equipped with a high resolution camera, as long as we could involve our Aquanauts in the mission," said Babb. The Aquanauts program, which Babb co-founded in 1988, has offered thousands of high school students and teachers over the years the opportunity to participate in hands-on oceanographic research. For this trip, two high school students and four teachers were selected. On July 27, the Connecticut, the Center's crew and the Aquanauts joined a host of experts from the Sanctuary, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the Massachusetts State Archaeologist to locate the shipwreck. First, side-scan sonar, a device shaped like a torpedo, was towed four to five feet behind the research vessel as it passed over the area where the wreck was thought to be. Dennis Arbige, the sonar operator, worked with Babb in setting up lanes on the sea floor to be surveyed. During this process, acoustical waves emitted from the sonar strike the ocean floor and are reflected back to the device. The harder the object encountered on the floor, the more sound waves are bounced back, creating an image resembling a black and white photograph. The next step involved the remotely operated vehicle, usually referred to as an ROV. It travels through the water while receiving commands through a cable attached to the ship. This cable also powers the ROV's lights and camera. From "command central" on the Connecticut's deck, Craig Bussel piloted the ROV, while Peter Boardman navigated. Several video monitors were set up on the Connecticut for all to see history in the making. "The moment when we first started seeing something other than marine life come into view, everyone was saying, 'Look, look, here it comes!'" says Babb. Then, as the ROV got closer, they became quiet and just watched. "We could see the side of the ship, then parts of the paddle wheel and a steam vent. It was incredible, and one of the most exciting moments in my career in oceanography!" he says. But he also describes it as "a humbling experience" to realize they were looking at a graveyard for 192 people. While most of the hull and its two smokestacks are still intact, the ship's upper decks, where the cabins and dining rooms were located, are gone. The video, says Babb, has disproved theories that the ship struck a rock or collided with another vessel. During the two-day expedition, the ROV conducted three trips down to the wreckage. During its last dive, the robot became stuck in one of the many fishing nets that swathe the wreck. It took several hours, the expertise of its crew, and the technology of UConn's research vessel to save the ROV, which is worth more than $200,000. It was a "white-knuckle kind of moment," Babb says. Locating the Steamship Portland was part of NOAA's effort to search the nation's 13 marine sanctuaries for archaeological and other so-called "cultural" finds. Babb is hoping to team up with Stellwagen Bank for a series of expeditions to identify the dozens of wrecks thought to be in the vicinity, although no other sinking is associated with such a large loss of life. At the end of their trip, Babb says the group held a moment of silence, and the Aquanauts cast flowers onto the water to remember the souls that perished more than 100 years ago. |

ne of New England's great maritime mysteries has been

solved, with the help of the National Undersea Research Center at

UConn's Avery Point campus and the University's research

vessel.

ne of New England's great maritime mysteries has been

solved, with the help of the National Undersea Research Center at

UConn's Avery Point campus and the University's research

vessel.