|

This is an archived article.

For the latest news, go to the Advance

Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. |

||||

|

Wagner

Finds Moths a Fertile Field

For Discovery, Classification By Elizabeth Omara-Otunnu To David Wagner, sleep is a nuisance. It's not just that like other scholars, he sometimes has to burn the proverbial midnight oil. His work demands that he stay up until all hours - for his research subjects fly by night. Wagner, an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, is an expert on moths. His specialty involves collecting, describing and classifying species, and detailing their life histories. He deploys his expertise in the interests of conservation and restoration ecology, sometimes raising live specimens in his lab, for study or release in the field.

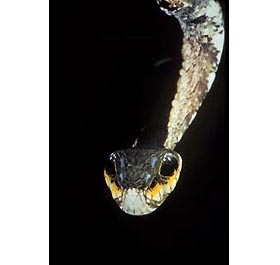

He collects extensively in the area around campus, and has a special mercury vapor light set up to attract moths to his own backyard. He also travels extensively to collect, and has special projects in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and in Costa Rica that sometimes demand all-night vigils. "It's so interesting," he says, "sleep gets in the way." Despite the showy allure of butterflies - creatures he describes as "brightly colored, day-flying moths" - Wagner says "moths are intellectually far more rewarding." With an estimated total of 250,000 species of moths in the world, there is great opportunity for discovery. "I see stuff almost on a daily basis that no one else has seen," he says. In the tropics, there are a few common species and an endless variety of rare species, he says. At the La Selva Biological Station, the rainforest site where he works in Costa Rica, 5,000 species of moths have been identified. "The biodiversity is out of this world," he says. "When you turn on the flashlight, your jaw goes down most of the time." But he is quick to point out that biodiversity is not confined to the tropics. During a BioBlitz in the Great Smoky Mountains in June - a 24-hour effort to inventory all the living species in the park - the species count for Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) alone was 860, including 51 species new to science. And last year, Wagner identified a moth there that was not only a new species, but represented the first time that its particular genus and tribe had been found in the New World. "There are still major discoveries to be made," he notes. Wagner's focus is on primitive moths - those that evolved in Mesozoic times, the era of the dinosaurs - and their coevals, dragonflies and damselflies. But his "true passion," he says, is caterpillars. He authored a popular 1998 USDA guide to caterpillars of the eastern forests. And this year, he and his colleagues published a second full-color guide, to caterpillars of the northeastern and Appalachian regions. The cover photos for his latest publication offer a clue to Wagner's fascination. The caterpillars depicted are extraordinarily well camouflaged. One mimics a stick. Another resembles a snake. "Each one is a reminder of the wonders of Darwinian selection," says Wagner. "These organisms are crafted by nature to resemble items inedible to vertebrates." Although insect collecting may have an old-fashioned aura, recalling its 19th century heyday, there's nothing passť about Wagner's work. His tools include a digital camera and the Internet; and he works closely with specialists in DNA analysis. "There has been a tremendous renaissance in my field in the last 20 years," he says. There are sophisticated new programs to make inferences about phylogeny - the evolution of groups of organisms. Reconstructing an evolutionary tree is highly complex, says Wagner: "For a small number of organisms, say 50, there are more ways to connect them than there are atoms in the universe." The science of phylogeny reconstruction has benefited from greater availability of DNA analysis, which has provided a wealth of new data, and ever faster computers that are able to deal with vast data sets. To the untrained observer, moths don't immediately appear a fertile field for the study of variation. Many look drab. "Color is not worth much at night," Wagner points out. But the myriad species of moth (there are more than 2,300 in Connecticut alone, compared with 127 species of butterflies) are differentiated in other ways. Nearly all possess pheromones ("bio-perfumes"), with scents ranging from foul odors to analogues of jasmine and cinnamon. "Moths have all kinds of structures for delivering scents from every part of the body," he notes. These scents are used in courtship, says Wagner, helping moths to identify and assess one another. There is also wide variation in genitalia among different species. If moths are to perpetuate their fragile existence, he says, "they don't want to hook up in the dark with the wrong species." Moths play an important role in ecology, says Wagner: "They indirectly enrich our world in a multitude of ways." Their caterpillars are an important food source for many vertebrates, for example, especially birds. "The Connecticut spring would be almost completely silent without moth caterpillars," he comments. Moths also - literally - add spice to life. "Caterpillars put pressure on plants to protect themselves," says Wagner. "The plants can't get up and walk away from caterpillars eating them, so many produce chemical compounds as protection." These compounds include most spices, and the tannins that are in red wine, as well as latex rubber. "It's an arms race," he says. "Plants and insects are co-evolutionary. Plants come up with something, then the insects break the fence, then the plants come back with some other toxic compound the herbivores must circumvent." But while evolution has taken eons, human intervention is changing the ecology at a very different rate, giving a sense of urgency to much of Wagner's work. "Some rain forests may not be here in a decade or two," he says. "There's an immediate need for properly preserved specimens that can be mined for DNA for decades down the road, maybe centuries, long after the rain forest is gone." Wagner says one of his goals is to share his knowledge with people in Latin American countries, so they too become participants in rain forest conservation. He plans to make the field guide he is developing for the 5,000 species of moths at La Selva, Costa Rica, available without charge online. Habitats are also at stake in Connecticut, where changes in land use - especially the transition from agriculture to forestation and development - threaten many species. About 40 species of butterflies and moths historically known in the state have disappeared or are in peril - one of the highest rates of loss in the nation. The outlook is no better, he says: "We're going to lose a lot more over the next few decades. Everybody likes to build a new house and own a plot of land." And that's reason enough for a biologist to lose some sleep. |