|

This is an archived article.

For the latest news, go to the Advance

Homepage

For more archives, go to the Advance Archive/Search Page. |

||

|

Speaker

Says Media, Parties, Electoral

Structure Causing Voters to Vanish By Richard Veilleux

Patterson surveyed more than 100,000 people for a study of public participation in the 2000 election campaign. Although his results won't be published until September, on April 11 he gave a group of UConn students, faculty and staff a preview of his book.

The villains in the story - the political parties, the media, and the structure of the country's system of electing leaders - are not new. Neither is Patterson's view that things will get worse before they get better. What is new is the vast amount of data Patterson has collected to demonstrate those beliefs. "If you sat down and decided to make elections more people-friendly, you couldn't do a lousier job" than election officials have done in recent years, he said. Putting much of the blame on increasingly lengthy campaigns, which now begin more than a year in advance of presidential elections, Patterson said his surveys indicated voters are not ready to start thinking about the election when the process begins; they've had too much of it by the time it ends; and most citizens are disenfranchised long before campaigns reach a critical stage. "The first debate (of the 2000 elections) was held three months before the New Hampshire primary. It drew about 1 million viewers. At the same time, on another channel, the World Wrestling Federation drew four times that many viewers," Patterson says. "There is a rush of interest after New Hampshire and through Super Tuesday a month later, then ... the election's over! You still have 30-35 states to go (before the party nominating conventions), but there's nowhere to go. These people don't really get to cast a vote or play a meaningful role in the campaign." The crux of Patterson's surveys lay in three questions: Did you talk about the campaign today? Did you read anything about it? Have you thought about it? In each instance, he found people who lived in states with early primaries or "battleground" states were far more likely to pay attention throughout a campaign. So were the declining number of people who identified with either party (30 percent of those questioned in 1999-2000 had nothing to say about what the parties stand for, compared to only 10 percent in 1952). "As we've moved away from the party system, we've stopped thinking about [elections], and that's led to people pulling away from the polls," he said. "It makes perfect sense. If you're a Red Sox fan, you're more likely to pay attention to baseball. If you identify with a particular party, you're more like to pay attention to the campaign." The political parties, he said, are victims of the way society has changed. "In the 1960s it was easy - the Democratic Party was for the working people, the Republicans represented business and the middle class. It was pretty easy to understand," he said. "Today, though, there are scores of issues, the terrain changes from election to election, and the number of issues increases. It's much more difficult for the voter to get his arms around." Patterson added that the people surveyed had a distaste for negativity. Yet that isn't something for which the politicians are primarily responsible. "During the 2000 election cycle, the journalist's voice was heard 75 percent of the time, compared to 12 percent for the candidates. And the journalists are much more genre centered, discussing strategies, and being very critical of the candidates," he said. "During the Kennedy-Nixon race, only 25 percent of the news was negative. It's been increasing ever since, and was negative more than 60 percent of the time during the 2000 election. Who was saying good things about the candidates during the Nixon-Kennedy race? They were: Nixon, Kennedy, and their running mates. As the media voice took over, so did the negativity," he said. Unfortunately, while all the answers to the decline in people voting are easy to see, Patterson said he doesn't anticipate changes happening soon, because all those involved are focused on their own self-interest. He noted that the New Hampshire primaries will be earlier next time and the Democrats are pushing to have Super Tuesday one week later, instead of the current one-month wait. "Why? Because they can't compete against President Bush in fund raising, so they want to keep the primary fights shorter. "Nor are television stations likely to put the debates back in prime time," he said, "because they can charge more for their commercials during a sitcom than they can during debates." Patterson said the system is increasingly run by specialists. "The opportunities for the little guy [to be involved in elections] increasingly are not there." Consequently, he added, come the first Tuesday in November, the "little guy" is not going to be in the voting booth, either. |

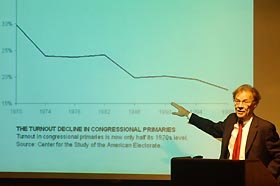

he pundits have had their say, over and over again, about

why the number of Americans turning out on election day has

declined in virtually every election cycle since 1960. Now, the

people are about to have their say. And the pundits, it will be

shown, are part of the problem, according to Thomas E. Patterson,

the Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press at Harvard

University and director of the Vanishing Voter Project.

he pundits have had their say, over and over again, about

why the number of Americans turning out on election day has

declined in virtually every election cycle since 1960. Now, the

people are about to have their say. And the pundits, it will be

shown, are part of the problem, according to Thomas E. Patterson,

the Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press at Harvard

University and director of the Vanishing Voter Project.